On the third day of January 1938, the city awoke to a typical cold dark morning. Sunrise was at 7:35 a.m., but the temperature stayed below freezing under cloudy skies with intermittent snow flurries.[1] It was the first workday of the ninth year of what would come to be called the Great Depression and no one could foresee an end. In homes across the city, either the husband or wife, or perhaps an older child, rose early to stoke the basement furnace, shoveling fuel from the coal bin to stave off the cold.[2] Breakfast was early for family members with jobs, especially those who walked to work to save on streetcar fare.

Education was not compulsory but most six-to-twelve-year-olds attended neighbourhood schools. Few continued on to high school or classical college as they were needed to contribute to the family income or assist with childcare. Wives might also seek paid employment, including piece work for the garment industry, but those with young children focused on the daunting task of household management on a limited and uncertain income.

Precise statistics on occupation, employment and income (as distinct from wage rates) are difficult to establish. Before the Depression began, 40 percent of the 932,000 people who lived in the city were part of the paid labour force, including large numbers who were seasonally unemployed.[3] Women, the majority under twenty-five years of age, made up 17 percent of those earning wages or salaries in 1931. Their average incomes were 50–60 percent less than males, or 40percent less when the comparison is by age groups.[4] A large number of twelve-to-fourteen-year-olds, of both sexes, were employed but uncounted in official statistics.

Despite a declining birth rate and efforts to settle people in Northern Quebec through colonization schemes and rural credits, Montreal continued to add new residents. An average of 5,800 families containing 27,500 people were added to the population each year so that by 1938 more than 1.2 million households lived in the city and its suburbs.[5]

Two thirds of Montreal’s citizens survived on marginal and uncertain incomes before the Depression began. The Montreal Council of Social Agencies’ 1928 report on wages and the cost of living noted that the Department of Labour’s budget for a family of five, $91.81 per month, was beyond the reach of most wage earners who earned less than $65.00 a month. Since the basic budget excluded expenditures for clothing, health, water, amusements of any kind and much else, poverty was widespread.[6] The cost of living declined during the 1930s and by 1938 the basic budget was priced at $85.00 but both wages and hours of employment had also dropped.[7]

Denyse Baillargeon has tried to describe the ways in which Depression-era families coped with this situation in her book, translated as Making Do: Women Family and Home in Montréal During the Great Depression.[8] Based on interviews with thirty women born before 1913, who managed family economics in the dark years, the book draws a detailed picture of survival techniques. Baillargeon’s interviews were with French Canadian women but the stories are similar to those of English-language, Italian, Jewish and Ukrainian families.[9] Across the city and beyond its cultural divides, coping mechanisms included a reliance on family or community gardens, boarders (usually relatives), assistance from extended family, income from children’s work from age twelve and long experience of living with limited expectations. Paid work for young women was more and more restricted as the Depression wore on unless they were willing to become domestic servants, the one occupation for which there was strong demand. Entering service usually meant living-in, with room and board, but salaries were so low that there was little left to contribute to a family. In 1936, the National Council of Women called for a household worker law with a minimum wage and overtime after sixty-four hours, but no action was taken.[10]

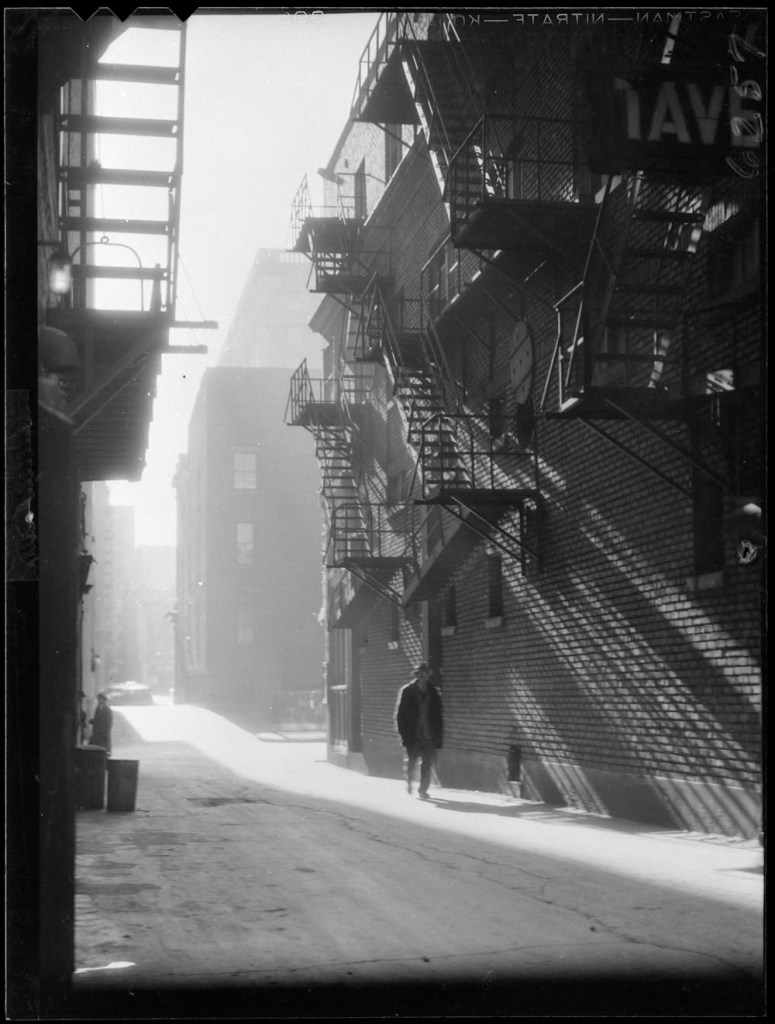

Families of the unemployed faced much worse challenges. The much-heralded recovery of 1937, associated with Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Dealexpenditures, brought unemployment below 20 percent but the effects of the so-called “Roosevelt recession” of 1938 were felt in Canada as early as September 1937. The Labour Gazette monthly report on Montreal noted, “a considerable decline in employment especially in textiles, leather and steel.”[11] As winter closed in, seasonal layoffs and a sharp decline in new construction added thousands to the relief rolls. In 1938, Montreal provided male heads of families who were “long-term residents” of the city with $41.38 a month, less than half of the Labour Department’s basic budget.[12] The rent portion of the relief allotment was paid directly to landlords leading to an increase in sub-standard housing. A committee of the Civic Improvement League, chaired by the architect Percy Nobbs, discovered that 17 percent of the 190,000 dwellings in the city were rented to 38,000 families on relief. “Bad housing” Nobbs maintained, “is often profitable to landlords but never to the community.”[13]

Montreal had begun an experiment in socialized medicine in 1936 when doctors who agreed to participate were paid out of a fund which provided 25 cents per person, per month to pay for treatment for relief recipients.[14] None of these modest welfare measures were available to the thousands of unemployed who were excluded from municipal relief including:

non-residents, recently deserted women with families, childless couples, separated women who do not have legal separation papers, other individuals about whom there is suggested immorality and individuals who are suffering chronic or even temporary disability but are able to do light work.[15]

Those who were judged to be unemployable due to age or infirmity were also excluded but the largest number of those who had to seek assistance from religious or secular charities were recent arrivals to the city. This measure, intended to discourage in-migration, created exceptional hardship but remained unaltered. Montreal social workers described these newcomers as:

a large body of single individuals and family groups who had nowhere to turn for help. Private social agencies, churches, missions, refuges and even private individuals were assailed from all sides. The security of the relief recipient was threatened with disastrous results. Begging increased, health was impaired, furniture and household goods were seized, as families were evicted and still the need was not met[16]

For single men the Meurling Refuge was the place of last resort. Doors opened each evening at 6:00 p.m., closing an hour later as the building filled. Clothes were disinfected while a compulsory bath was taken. The daily meal, which never changed, was “leavened bread and bologna with tea or coffee.” “After eating, in strict silence, the men go to their beds…In the morning they must get up at 6 o’clock, take a light breakfast, and by 8 o’clock everyone must have left the refuge…”[17] Conditions at the Old Brewery Mission and in church basements across the city were less strict, but the men were still required to move on in the early hours of the morning. The Montreal Council of Social Agencies rented a large, previously closed school, where men could read, play games and sports, and attend classes.[18] Hundreds of men, a small fraction of the city’s unemployed, used the facility each day while the rest sought shelter where they could.

Montreal’s infant mortality rate had plummeted during the 1920s as milk pasteurization became standard practice and new methods of treating babies suffering from gastroenteritis and dehydration were introduced. Dr. Graham Ross and the pediatric service at the Royal Victoria Hospital, led the way and other hospitals soon followed, treating infants with fluids given subcutaneously or intravenously.[19] At first the change was most noticeable in the west end, but by 1938 there was progress in the outer wards and east end, though infant mortality rates were still double those in the better off districts.[20] Links between poverty, substandard housing and ill-health were also evident in the varying rates for tuberculosis (TB) and other infectious diseases across the city. By 1938, physicians understood that the only effective method of limiting TB was to identify and segregate active cases, preventing the infection of others—an objective more difficult to attain in the crowded working-class wards.[21]

One of the most under-reported aspects of life in the depression years was the impact of impoverishment on children and adolescents. Leonard Marsh, the Director of Social Research, McGill University, outlined this problem in his book Health and Unemployment, devoting sections to “Juveniles and Adolescents”, and “The Family”.[22] The “juvenile sample” was obtained with the cooperation of the Y.M.C.A. and the Montréal Boys Association. The sample was, therefore, “mainly English-speaking.” Announced as a health check-up, the notifications attracted 270 volunteers whose average age was seventeen. Three-quarters had been born in Montréal. Just twelve stayed in school beyond Grade 9 and most left by the end of Grade 7.

A majority had worked at odd jobs and various kinds of unskilled labour. Messengers, garage helpers and newsboys figured frequently in occupational histories. Few aspired to office work or claimed an education sufficient for business life, here and there a forceful character appeared, whose ambition was not dulled by many defeats and who was striving towards a position in life which he felt bound to open when the depression lifted. Such optimism was rare.[23]

The examination covered issues such as nutrition, condition of teeth, vision, hearing, disease and general health. High rates of “rheumatic complex” (22 percent), cardio-vascular weakness (8.5 percent) and infected tonsils (16 percent) were recorded. Marsh also used a survey of student heights and weights compiled by the Montreal Protestant School Board which indicated that children of lower income families were two inches shorter at seven years of age and five inches shorter at age fifteen than their higher income peers.[24]

Marsh was not able to investigate other aspects of childhood in the 1930s. One situation, the plight of orphans who were required to leave institutions when they turned fourteen was particularly difficult to grasp. According to a report in La Patrie, Montréal had thirteen orphanages for girls with a waiting list of over 500. Each year 400 girls were “put on the street” because government funding was not available for fourteen-year-olds. The situation for boys was similar with even larger waiting lists and close to 500 released each year as they turned fourteen.

Church leaders, Protestant and Catholic, were more concerned with the moral dangers facing the young than their physical well-being. Convinced of a rise in juvenile delinquency and more serious crimes among older youth, they campaigned to end the “corruption of youth”.[25] Le Fédération des Ligues du Sacré-Coeur committee on morality was particularly vehement about the situation in Montreal, calling for a new Juvenile Morality Squad to deal with the “shocking problems facing its city”. Delinquency was said to have doubled during the depression, more than 2,500 seventeen-to-twenty-one-year-olds were being sentenced to serve time in the Montreal jail each year. More than 90 percent found guilty of “thieving” but the Ligue focused on sexual morality claiming that “five to six times the amount of venereal disease is being spread by juvenile delinquents than by prostitutes.” Police Director Dufresne was said to be particularly concerned with “unnatural vice”.

Despite the great difficulty of securing evidence and convictions in crimes of unnatural vice detectives had placed offenders behind bars…with little publicity because of the unprintable nature of the crimes and the injustice of dragging the names of the victims and relatives of the victim and accused alike into print.[26]

The suburban City of Verdun, which had used the local option to ban the sale of alcohol, tried to address the challenges of youth culture by operating a large dance pavilion. Designed with a dance floor separated from the rest of the rectangle by a low railing, teenagers and young adults could dance or mingle and flirt while watching the dancers. No doubt hip flasks were brought to the pavilion, but the attraction was big band music. After the Verdun Auditorium, a relief project financed by the Duplessis government in 1938, opened dances with free admission that were held twice a week through the winter.[27]

Efforts to improve wages and working conditions through unionization continued throughout the 1930s aided by the passage of the “Arcand Act” in 1934. Named for the Minister of Labour in the government of Alexandre Tashereau, Joseph Arcand, the Quebec Collective Labour Agreements Act, allowed the provincial cabinet to issue a decree extending the provisions of any collective agreement to the entire industry in a designated region. The Act required the creation of a joint worker-management committee, legally incorporated, to enforce the terms of a decree governing wages, bonuses, apprenticeships and the proportion of skilled and unskilled workers. While no provisions relating to union recognition were permitted, unions quickly took advantage of this opportunity to attract workers in the city’s main industries and service sector.[28]

The city’s garment industry with over 11,000 workers in women’s clothing, 5,500 in men’s clothing and 1,400 making hats and caps was by far the largest employer. International unions, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers, the International Ladies Garment Workers’ Union and the United Hat, Cap and Millinery Workers were all active in Montréal organizing locals in the hope of winning wage increases and the closed or union shop. A bitter war, marked by frequent strikes, was waged in the garment district. The Amalgamated Clothing Workers (A.C.W.A.) and the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (I.L.G.W.U.) were both struggling to keep their locals alive in a situation where union agreements were almost impossible to maintain. From 1934, in the case of the A.C.W.A., and 1937 in the case of the I.L.G.W.U., the local labour situation was stabilized in the sense that these two unions were unchallenged in the industry and had organized their own joint boards to coordinate the activities of the constituent locals.

This did not mean that the clothing industry had been successfully unionized. The Amalgamated still faced the daunting prospect of organizing workers who were without jobs six to eight months of the year and could consequently be tempted to take any available work at almost any wage. The clothing manufacturers also tried out-of-town contracting in cities such as Sherbrooke to avoid union rates. Six months after the A.C.W.A.’s “successful” recognition strike of September 1933, 4,000 workers were out for ten days in an abortive attempt to win the forty-hour week and the union shop.[29]

It was in the context of an ongoing struggle that the Amalgamated agreed to a judicial extension of the wage and hour provisions of its agreement to the entire industry in the province (February 1935). In theory non-union shops would henceforth be required to pay union level minimum wages. The battle was now to be focused on union agreements and in September of 1935 the A.C.W.A. supported a month-long strike against one firm winning a closed shop for 900 workers. Three more such strikes were won in 1937, and one in 1938. The A.C.W.A. enjoyed relative success in the late 1930s, but its wage gains were modest and large parts of the industry were left unorganized.[30]

The Arcand Act had played a significant role in the development of the Amalgamated in Montréal. Government regulation of wages and hours allowed the union to focus its energies on recognition and to gradually expand its base. The union was thus in an excellent position to seize the opportunity presented by the war.

**********

What role did the provincial government play in the life of Montreal in the depression decade? Montreal, like all Canadian cities, was a creature of the provincial legislature and required the consent of the government to raise taxes or borrow money. The Premier of Quebec claimed to approach governance on the basis of Catholic social doctrine, as outlined in the Programme de restauration sociale, an initiative of the Jesuit-sponsored Ecole sociale populaire.

His Union Nationale party had absorbed the various nationalist groups that came together as Action Liberale Nationale and marginalized the ALN by excluding its leaders from his cabinet. Duplessis, in the words of Lionel Groulx, was not “the saviour of his people” but “a pragmatist who lacked the will of a Dollfuss, Salazar, or Mussolini”[31]

Duplessis paid little attention to the intellectuals who endlessly explored the contours of the national question and the reasons for the economic inferiority of French Canadians. He did however address the priorities of his rural voting base. The Provincial budgets included dramatic increases in ordinary and capital expenditures, doubling the provincial debt in just a few years. Almost all of the additional expenditures were directed at agricultural credit, rural construction, colonization schemes and the caise populaire movement. Funds were also found for a new Ecole des Mines at Laval University and the province’s share of the cost of the Federal-provincial agreement on education programs for unemployed youth. A school for aviation technicians was announced, to be located in Montreal and to train youth in aircraft maintenance and machinist skills, but little was accomplished before the war.[32]

Duplessis also claimed credit for Quebec’s delayed participation in the Canada Old Age Pension Act. The province was responsible for 25 percent of the cost of a plan that provided an annual pension of $300.00 to persons over seventy who had resided in the province for five years and in Canada for twenty. No one with an income exceeding $425.00 a year was eligible and for those whose income exceeded $125.00 the excess amount was deducted from the pension. Individuals defined as “Indians” under the Indian Act were not eligible.

The Needy Mothers Allowance Act, introduced in 1937, provided $35.00 a month for a woman with children whose husband was deceased, absent, disabled or imprisoned. Mothers were to satisfy the administration of a “reasonable guarantee of good conduct and competency to give the children care of a good mother.” The first payments under the Act were made in December 1938.

Duplessis won support from the large majority of Quebecois with an “Act Respecting Communist Propaganda” which passed the legislature in March of 1937. The measure, designed to circumvent the criminal code, allowed Duplessis as the Attorney General, to “close any house used to propagate communism or bolshevism” for a period of one year and to “seize, confiscate, and destroy” writings “propagating or tending to propagate Communism or Bolshevism.” The only substantial criticism of the legislation came from Peter Bercovitch, the Liberal member for Montreal St. Louis, who protested the failure to define Communism and sought the inclusion of Fascism and anarchism in the law as they were equally dangerous to democracy. “Not to Quebec”, Duplessis replied. [33]

The law, known popularly as the Padlock Act or loi du cadenas, was first used in November 1937 when the French language, Communist Party newspaper Clareté was suppressed. When a delegation of labour leaders met the Premier to protest, Duplessis declared “This is only the beginning of our activities” and warned them to purge their own ranks of communists. He added that the closed shop would not be tolerated in Quebec and locals of the CIO (Congress of Industrial Organizations) would not be entitled to benefits in the Collective Bargaining or Fair Wage Acts.

As the Attorney-General, Duplessis ordered frequent raids on the homes and offices of those suspected of communism. If books or pamphlets judged to be communist or copies of Clareté, which were now printed in Toronto and smuggled into Quebec, were uncovered the premises were padlocked. The Modern Book Shop, a project of young communists, was an obvious target.

The government of Canada played an equally marginal role in Montreal. Apart from paying some of the relief costs, Canada’s cities were left to cope with the Depression independently. The King-Lapointe ministry, returned to power in 1935, had won all but the five English-language ridings in Quebec without making any promises about urban issues. Apart from tinkering with the tariff and negotiating a new trade agreement with the United States they were prepared to wait out the hard times, preserving Canada’s credit rating.

The apparent recovery in 1936-37 seemed to justify this approach though unemployment remained high. As late as January 1938 the throne speech boasted of a “substantial advance in economic recovery.” The government, apparently satisfied with the situation, announced that the report of the National Employment Commission would be tabled in due course and a new Royal Commission, “to examine the financial basis of Confederation and the distribution of legislative power” under the chairmanship of Newton Rowell and Joseph Sirois was underway.[34] The Commissioners met a virtual boycott in Quebec, and Montreal’s civic administration followed Duplessis’ example.[35]

By June of 1938, Finance Minister Charles Dunning could not ignore “the drastic reversal of world economic trends.” Canada, he admitted, has suffered a significant decline in business activities while drought conditions in the prairies indicated a 50 percent reduction in the wheat harvest. Dunning tried to find positive signs noting that national unemployment had declined to 456,000 men and women while the number registered for relief in the cities was 120,000 less than in 1937.[36]

The cabinet did agree on one major initiative, a guarantee of eighty cents per bushel for Prairie wheat producers. A year later, three months before the outbreak of war, Dunning’s budget speech lamented that: “Recovery has on several occasions raised its head only to be buried again in a new wave of uncertainty.” The Canadian economy, he reminded parliamentarians, is “based in agriculture, forestry, and mines and was dependent on world trade.” The large budget deficit predicted for 1939-40 was due to the wheat price guarantee and low-level private investment. “A balanced budget must be deferred.”[37]

Citations

[1] Montreal Daily Star (afterwards the Star), January 4, 1938.

[2] With my father frequently working away my mother shovelled coal into our furnace many mornings.

[3] Labour Gazette, 1938, p. 57.

[4] Percy Nobbs. A Survey of the Present Location of the Housing of the Unemployment in Montreal (Montreal 1937). p. 6.

[5] Nobbs, p. 6.

[6] Montreal Branch, Canadian Association of Social Workers, The Realities of Relief (Montreal 1938) p. 14.

[7] Nobbs, p. 9.

[8] Denyse Baillargeon, Making Do: Women Family and Home in Montreal During the Great Depression (Waterloo 1999).

[9] Jeanie Kurylei, Surviving the Depression in Montreal (Unpublished seminar paper, Concordia University, 1974)

[10] Cited in June MacPherson’s “Brother, Can you Spare a Dime:” The Administration of Unemployment Relief in Montreal 1931-1941, (Concordia University, 1974).

[11] Labour Gazette, September 1938.

[12] MacPherson, p. 24.

[13] Nobbs, p. 9.

[14] MacPherson, p. 38. See also Libbie Park “The Bethune Health Group” in David Shepherds and Andree Levesque (eds) Norman Bethune: His Times and His Legacy (Montreal 1982).

[15] MacPherson, p. 24.

[16] The Realities of Relief, p. 14.

[17] Ibid, p. 36.

[18] Susan Markham, Recreation and Sport as an Antidote to Economic Woes: The Great Depression in Canada, p. 3 Online.

[19] Jesse Boyd Scriver, “The Royal Victoria Hospital, Montreal Common Diseases in the 1920s and 1930s” Levesque, Bethune.

[20] Benoît Gaumer et all. Histoire du Service de santé de la ville de Montréal. 1865-1975, (Quebec 2002), p. 161-164.

[21] Katherine McCuaig, “From a Social Disease with a Medical Aspect to a Medical Disease with a Social Aspect: Fighting the White Plague in Canada” Bethune, p. 54.

[22] Leonard Marsh, Health and Unemployment (Montreal 1930)

[23] Marsh, p. 99.

[24] Marsh, p. 141.

[25] Montreal Daily Star, 7 April 1939.

[26] Montreal Standard, 6 May 1939.

[27] Robert Simpson, “Light Fantastic: An Account of the Verdun Dance Pavilion” (Montreal 2009) Online.

[28] Terry Copp, “The Rise of Industrial Unions in Montreal” Relations Industrielle. See Appendix A.

[29] Lionel Groulx, Mes Memoires, Vol. 3, p. 260.

[30] Christine Blais, Histoire parlementaire du Québec, 1928-1962, (Quebec 2015).

[31] Quebec Statistical Yearbook, Vol 3 200-211, 1943 p. 225-229.

[32] Blais, p. 227.

[33] P. 227

[34] Canada, Debates of the House of Commons (Hansard 18th Parliament, 3rd Session, Vol. 1 1938), p. 2.

[35] Blais, p. 259.

[36] Canada, Hansard, 16 June 1938.

[37] Canada, Hansard, June 1939.

One thought on “Chapter I – Metropolis”

Comments are closed.