Most Montrealers who earned wages rather than salaries shared a common experience with low incomes shaping much of their lives. There were however other realities determined by religion, language and ethnicity that linked people across class lines, creating a city that was divided by profound cultural differences. For more than 60 percent of the population, the Roman Catholic Church and the French language were central to their identity and collective memory. Frequently, if not regular attendance at Mass, children educated in unilingual clerically controlled schools, friends or relatives who were members of religious orders all contributed to French Canadian solidarity. Hospitals, welfare institutions, classical colleges and universities were owned and operated by the Church, indicative of a society that had a higher ratio of clergy to the faithful than Italy or Spain.[1]

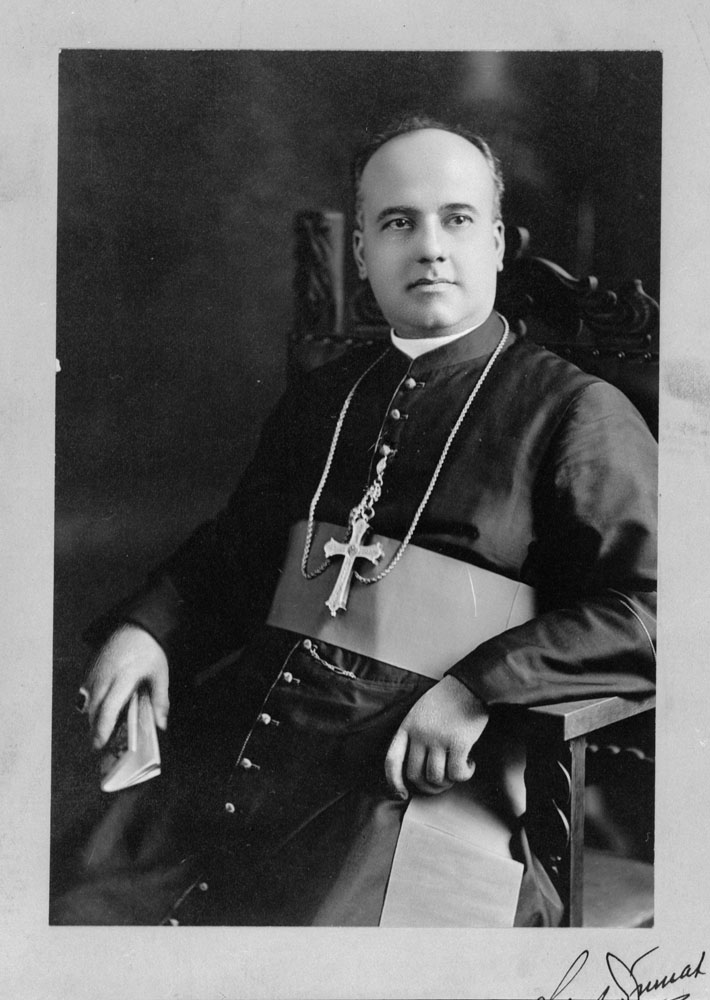

The Archdiocese of Montreal was administered by Bishop Georges Gauthier who was born in 1871 and ordained in 1894. After doctoral studies in Rome and a series of important appointments, Gauthier became the city’s Auxiliary Bishop with the right of succession in 1918. When Archbishop Paul Bruchesi succumbed to dementia the following year, Gautier led the Archdiocese until his death in 1940. Described by his biographer, Denise Robillard, as a “studious, reflective, and highly cultivated man… with the gift of a vibrant voice that helped to make him a powerful, effective, and convincing speaker.” Gautier was involved in most aspects of Montreal’s religious, cultural, and political life.[2] Like other members of the Catholic hierarchy, Gautier was influenced by Pope Pius XI’s decision to make the fortieth anniversary of the encyclical Rerum Novarum with a restatement of Catholic social doctrine, Quadragsimo Anno. This 1931 encyclical repeated much of Rerum Novarum adding a specific and detailed denunciation of communism which had emerged as a powerful force in Italy.

The Pope described an alternate world overview based on cooperation between workers and employers who together were to promote the common good. The right to private property was upheld but Pius distinguished between ownership and the use of property and capital. A “male worker”, he wrote, “must be paid a wage sufficient to support a family.” Employment for women and children was to be avoided. Cooperation between employers and workers was most readily accomplished through the development of guild-like syndicates uniting capital and labour. Strikes and lockouts would be unnecessary and forbidden. Since the state must be subordinate to the church, government functions were to be exercised at the most local level possible.[3]

Gautier believed in and preached Catholic social doctrine. In a 1934 pastoral letter, occasioned by the formation of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation or CCF, Gautier, noting the Regina Manifesto’s pledge to “eradicate capitalism,” forbade Catholics from joining the new party. Socialism, he declared, “is the precursor of Communism.” Gautier also shared the general French Canadian aversion to feminism declaring it was a “sickness which must be cured by workings other than those of politics.”[4]

There were however other sides to Gautier. As the first rector of the newly independent University of Montreal, he transformed an institution dedicated to the education of priests, lawyers and physicians into a modern university. Faculties of science, dentistry, veterinary medicine, philosophy (detached from theology) and a School of Social Science, Economics and Political science directed by Édouard Montpetit, the first lay person to lead a faculty at a Quebec Catholic University. Later, as university chancellor, he led the campaign to build a new campus on the north slope of Mount Royal. Construction began in 1928 but neither Church nor state or private philanthropy was able to fund the ambitious project in the 1930s. The partially completed campus did not open until 1943 two years after Gauthier’s death.[5]

Gauthier also tried to encourage the development of secondary education for French-speaking Catholics. English-speaking Catholics followed the lead of the Protestants who established high schools that provided their students with four years of secondary school leading to a junior matriculation with direct entry into university or the workforce. In French Catholic Quebec university entrance was limited to graduates of classical college, so the new “Superior Primary” schools for fourteen-to-sixteen-year-olds provided a general education for entry into commerce, public service and industry. Unfortunately, the depression curbed the planned expansion of the schools which continued as fee-paying institutions largely unavailable to working class families.[6]

Gauthier was also responsible for the introduction of Jeunesse Ouvrière Chrétienne to Montreal. Established in Belgium, the movement spread to France and other European Countries as a Catholic response to radical, particularly communist, youth organizations. Gauthier asked Father Henri-Roy, an oblate worker-priest, to visit the European leaders and establish groups in Montreal’s east parishes known as Jeunesse Ouvrière Catholique in Quebec. The Jocistes, as they were called, developed quickly thanks to Father Roy’s inspired leadership. Both female and male groups began to plan concrete actions to promote the faith and welfare of working-class parishioners.[7]

The movement’s monthly journal La Jeunesse Ouvrière presented articles on religion and the menace of communism, but its pages were also filled with accounts of Jociste activities: prison visits, food and clothes for the unemployed, a placement service, free dental care and summer camps. By 1939 more than 40,000 men and women were Jocistes, active throughout the province. Their 1939 congress included a mass wedding of over one hundred couples held in Delorimier Stadium during a July heat wave. Gautier and hundred-plus priests married the couples who had graduated from a course on marriage and the family.[8]

The success of the Jocistes, which attracted far more participants than the various nationalist groups, encouraged Gautier to import a second specialized Catholic Action organization from Europe, Jeunesse étudiante chrétienne. He once again bypassed the Jesuit-sponsored Association Catholique Jeunesse Canadien (ACJS), placing the Jedistes under the tutelage of the Fathers of the Holy Cross. The emphasis on Catholic action rather than traditional clerical nationalism drew the ire of Abbé Groulx and his followers who condemned separating nationalism from Catholicism.[9]

Both Catholic action and nationalist organizations had to compete with the extraordinary cult of Brother Andre and his shrine atop Mount Royal. André Bessette, a lay brother of the congregation of the Holy Cross, served as a porter at the order’s Collège Notre-Dame. Brother André’s reputation as a healer of the sick spread throughout the city and, in 1924, construction on a basilica, St. Joseph’s Oratory, was begun. When Brother André died in 1937, hundreds of thousands paid their respects and the oratory became an important pilgrimage site.[10]

Twenty-two percent of those who lived in Montreal and its suburbs were Protestants who spoke English as their first and usually only language.[11] Most lived in west-end districts and independent municipalities where contact with French Canadians was limited and infrequent. The Anglican Church of Canada with 99,782 adherents was the largest denomination. The Anglican Bishop presided over a church with a common doctrine that allowed room for Anglo-Catholic traditions and “low church” protestant practice. Arthur Carlisle, the popular Dean of Christ Church Cathedral, succeeded John Farthing (1909-1938) as Bishop in 1939. Carlisle had served as a Chaplin in the First World War and like many others, developed pacifist sympathies which endured until the full nature of the Nazi threat was apparent.[12]

The United Church of Canada, with 54,063 members, and the Presbyterians with 40,595 members, were voluntarist churches where congregations selected and removed ministers resulting in a wide range of opinions. The religion pages of the three English-language dailies illustrated the diversity of Protestantism, especially on Saturdays when display ads for Sunday services and select stories were published.

By 1938 differences of opinion over evangelism, the social gospel and the responses to the threat of war were evident among the ministers and theologians of all Protestant denominations. It is not clear how much this mattered to those who attended Sunday School, young people’s meetings or the hour-long weekly service. Most Protestant churches sponsored Boy Scout Troops, Girl Guides and the Canadian Girls in Training (CGIT). Much energy was also devoted to foreign missions, total abstinence campaigns and relief work. The Young Men’s and Women’s Christian Associations were closely allied with the churches providing athletic facilities, a residence and evening classes in both vocational and university-level courses through Sir George Williams College, houses in the downtown “Y”.[13]

The city’s Protestants were divided on Sunday, but the interdenominational education system brought them together for elementary and high school. Fees were still charged for grades 10 to 12, but the first nine years of school were free. Under the influence of John Dewey, the Protestant School Board of Montreal and the other local boards introduced kindergarten, music, industrialist arts, school libraries and much else to create a more activist, child-centred education. W. P. Percival, the provincial director of Protestant education, described the development in two well-illustrated books Life in a School (1940) and Across the Years (1946), both of which used numerous illustrations to document classroom and extracurricular activities.[14]

More than a thousand students in the Protestant schools wrote the High School Leaving Exam in 1939 many of whom hoped to attend McGill University. McGill’s international reputation, ranking it well above other Canadian universities, drew students from all across Canada and elsewhere, but 60 percent of the students were from the Montreal area.[15] During the 1920s the relatively small Jewish population in the city, whose children attended the schools as “honourary Protestants”, provided 25 percent of McGill’s Arts enrolment, 40 percent in law and 15 percent in medicine. The Board of Governors and Principal, Sir Arthur Currie, believed that this “Jewish influence” threatened the Protestant character of the university, so measures were taken to limit the number of Jews admitted by, “quotas in medicine and law and high matric marks in Arts.” By 1939, Jews accounted for 12.1 percent in arts, 12.8 in medicine and 15 percent in law.[16]

McGill weathered the Depression partly because the members of the Board of Governors agreed to cover the annual deficits. The university also added to its reputation as a research centre with financial support from the Rockefeller Foundation which played a major role in the establishment of the Montreal Neurological Institute under the leadership of Dr. Wilder Penfield. The MNI became a world centre in neurosurgery and neurology during the 1930s, further enhancing McGill’s reputation in both clinical and scientific research in medicine.[17]

McGill also had a well-established program in the social sciences, particularly sociology with Carl Davidson and Everett C Hughs. In 1933, the university established a separate research group “to encourage the scientific study of the ordinary problems of humanity.” Both Sir Edward Beatty, the Chancellor, and Currie supported the project and appealed to the Rockefeller Foundation for funding. Currie noted that the Quebec government had recently appointed a Royal Commission under the chairmanship of Édouard Montpetit which would, he thought, only employ academics from the University of Montreal and “will not amount to a row of pins.” McGill intended to study social problems based on evidence not Catholic social doctrine. A grant of $110,000 over five years was secured and Leonard Marsh was appointed as director. Leonard Marsh was twenty-four years old when he joined McGill. He had studied with William Beveridge at the London School of Economics and shared his mentor’s belief that the social sciences were “too theoretical, deductive and metaphysical.” What was required was empirical studies of social problems. For the McGill project, Marsh planned a series of studies focused on the unemployment crisis, especially in Montreal. Graduate students were to be employed as research assistants while completing their own work.[18]

Marsh, a Fabian socialist, believed that social reform required a full understanding of specific problems. His association with the CCF and work for the League of Social Reconstruction on the Manifesto Social Planning for Canada did not endear him to the McGill Board of Governors, but in 1936 the Rockefeller grant was renewed for five years, allowing a number of major projects to continue. The publication of Health and Unemployment (1938) and Canadian In and Out of Work (1940) further enhanced McGill’s reputation in the social sciences.[19]

The seventy-thousand English-speaking Catholics were a separate community with their own parishes, schools, social and charitable institutions. Due defence was paid to the Archdiocese and Bishop Gautier but Father Patrick McShane, the pastor of St. Patrick’s Basilica, the downtown mother church, was their real leader. New, publicly financed high schools, Darcy Mcgee and Daniel O’Connell, modelled on the Protestant system, were built in the prosperity of the 1920s opening as the depression struck. Together with the Catholic High School of Montreal and Loyola High School, a private Jesuit institution, they provided the kind of educational opportunities enjoyed by the Protestants including direct access to McGill and other universities.[20] The city’s Commission des ecoles catholique encouraged the development of English-language schools partly because of the fear that the presence of English-speaking students would encourage the use of English among French Canadians.

The Commission paid slight attention to the children of the small Italian population in Montreal. In 1936, one hundred and twenty-six[1] pupils of Italian origin were registered in French Catholic schools. Just 48 of the 2000 students who reached Grade 8 were Italian. Many Italian families sought to enrol their children in the Protestant schools to gain access to English-language instruction. A fee of $8.50 a year or signing a form converting to Protestantism for school tax purposes was required. In 1935, six hundred and sixty-two parents signed such a form, and the practice continued through the 1940s.[21]

Montreal’s Italians were concentrated in Mile End and enclaves in Point St. Charles, St. Henri and Lachine. By 1938, there were 25,000 men, women and children of Italian descent in the city, a little over 2 percent of the urban population. During the 1930s, a McGill graduate student, Charles Bayley spent seven months doing “field work” within these neighbourhoods allowing us to know their lives in some detail. Bayley’s thesis employs a classification of 6,377 adult Italians in Montreal based on the 1931 census. Twenty-one 21 percent were labourers, 16 percent were tradesmen, especially railway trades or semi-skilled construction and mechanical workers. The remaining third were employed in a variety of low-skilled occupations except for 137 men who Bayley, using a broad definition, classified as professionals. Occupation in 1931 should not be confused with employment, and by 1933 Bayley thought as many as 75 percent of Italians were unemployed. In 1936, 1,084 families or 4,293 individuals were receiving municipal relief and Bayley estimated that one-third of the city’s Italian families were “impoverished.”

As a sociologist, Bayley was interested in the cultural and associational life of the immigrant communities. Italians, he reported, joined the Order of the Sons of Italy, a mutual benefit society and a growing number of fascist organisations sponsored by the Italian Consul in Montreal. Mussolini had declared that Italians living overseas were still Italian citizens, liable for military service. His regime sought ways of establishing loyalty to the Duce and the fascist movement. When Montreal’s Italians gathered at the Casa d’Italia, which opened in 1936, for spaghetti nights, porchetta (roasted pork) feasts, dances (fox trot and swing), card games or sports, like the Italian team in the Montreal Senior Baseball league, they were likely to meet fascist consular officials.[22]

Such activities were bound to attract the RCMP Security Service’s attention, particularly after the invasion of Ethiopia. RCMP reports detailed the activities of consular officials and local leaders who promoted loyalty to Mussolini through a “takeover” of the Sons of Italy, the subvention of a weekly newspaper L’Italia Nuova, and the creation of a Canadian Fascio association whose membership was screened in Italy as well as Canada. A select number then joined the Centura D’Omore who wore black shirts and provided an aura of militancy.[23] Neither the RCMP nor the government took such activity seriously during a period when the British government attempted a reconciliation with Mussolini in the hope of detaching Italy from Germany.

Close to 60,000 Jews, 5 percent of the population lived in Montreal. Like their fellow citizens, they were preoccupied with the impact of the depression on their lives as unemployment, underemployment and continuing conflict in the garment district took precedence over issues such as rising antisemitism in Europe and Quebec. Montreal’s Jews were largely immigrants from Eastern Europe, with memories of pogroms common in Czarist Russia’s Pale of Settlement. Their first language was Yiddish, but children attended Protestant schools and English was commonly spoken. A small percentage of established, wealthier Jews lived in the west end, but the majority occupied rented “flats” in the centre-east wards astride St. Lawrence Boulevard, known as “the Main.”

Gerald Tulchinsky has described the city’s Jews as a “third solitude, almost a separate community” with its own institutions, culture, self-perceptions and public image.[24] Three newspapers, the Yiddish Keneder Adler (Jewish Eagle), the Canadian Jewish Chronicle and the Canadian Jewish News offer a detailed picture of the religious, cultural and ideological life of Montreal’s Jews.[25] The sources allow us to see events as they were understood at the time without imposing foreknowledge of the war or the Holocaust on the narrative.

News about the social and religious life of the community, the work of organizations like the Baron de Hirsch Institute which was active in education and welfare, the Jewish General Hospital and the Federation of Jewish Charities were reported in detail. The city’s Zionist organisations and the efforts of Jewish leaders to change Canada’s restrictive immigration policies were described as was the plight of European Jews and the conflict in Palestine. The British Royal Commission, appointed in the aftermath of the Arab uprising in 1936, recommended the partition of Palestine with a coastal Jewish state, an Arab state and a British-controlled neutral zone encompassing Jerusalem and Bethlehem. Most Arab and Zionist leaders rejected the proposal but in Montreal, the Chronicle argued that “we cannot afford to reject the project.” There was still time, the Editor insisted, to negotiate boundaries but the principle of the partition should be accepted.[26]

Throughout the fall of 1937 news of anti-Semitic measures, especially in Poland, prompted the Chronicle to consider the various schemes proposed to settle European Jews in Africa. If Poland or other areas with large Jewish populations succumbed to fascist movements millions of Jews would be endangered. An article titled “Does the Jewish State Need a Colony?” made the case arguing that the proposed state of Israel was too small to accommodate millions of Jewish immigrants who would need to be settled in Uganda or elsewhere in British-controlled Africa.[27]

The Canadian Jewish Congress and its President Sam Jacobs, the Member of Parliament for Montreal-St. Louis, tried to persuade the government to admit a greater number of Jewish refugees. Jacob’s friendship with Prime Minister Mackenzie King meant he always received sympathetic hearing but King avoided any action due to opposition from his key Quebec lieutenant Ernest Lapointe, the Minister of Justice. Lapointe in turn feared that any easing of restrictions against immigration, especially Jewish immigration, would strengthen nationalist elements in Quebec. Hitler’s annexation of Austria produced yet more Jewish Refugees but before Kristallnacht in November 1938 (discussed below) there was little public debate about the admission of refugees to Canada.[28]

The formation of Adrien Arcand’s National Unity Party in 1938 was reported, but Arcand and his small band of acolytes had been spouting hatred towards Jews since 1929. His “Blueshirts” were not exactly comic opera but neither the Jewish community nor the RCMP saw them as a serious threat. The Canadian Jewish Congress and the Chronicle knew the real enemy was to be found among the nationalists and their newspaper Le Devoir. Georges Pelletier, the journal’s editor, had outlined his views in a front-page essay in which he opposed all immigration to Canada but “especially Jewish immigration.”[29]

**********

One bright spot for everyone in the gloom of the 1930s was radio which grew in popularity and affordability throughout the decade. By 1938, a large majority of households owned a radio, often purchased on credit with payments as low as $4.00 a month for two years.[30] The CBC/Radio Canada were both well established with two stations CBM and CBF providing news, music, comedy and drama in the two official languages. The private stations CFCF (English) CHLP and CKAC (French) competed with a mix of popular American shows and local programs. French listeners enjoyed soap operas and dramas by Robert Choquette, Gratien Gélinas and many others. Newspapers also listed the schedules of the U.S. network stations within range of the city ensuring that Amos and Andy, Ellery Queen, Jack Benny, Edgar Bergan and other mass audience programs were available.

The most popular program was the Saturday night ritual “Hockey Night in Canada” which began in Toronto but quickly spread to Montreal. The initial game, played by the Montreal Canadians, was broadcast in French with English listeners following the fortunes of the Montreal Maroons. The Montreal Forum was originally built for the Maroons who won two Stanley Cups before economic conditions forced the owners to fold the franchise after the last season. The CBC then broadcast the games of the Canadians in both languages.[31]

Montreal was also a major market for Hollywood films and all newspapers carried ads and capsule reviews of new movies. The large downtown theatres showed films in their English versions attracting audiences from both language groups. Motion pictures almost killed Vaudeville but the French Canadian tradition of satirical reviews flourished especially after Gratien Gélinas introduced his character “Fridolin” to audiences at the Monument National. Fridolin was a street-smart, eternally optimistic boy of fifteen who made fun of daily life in the city. Beginning as a radio program in 1937, Gelinas produced the first of a series of comedy reviews called “Fridolinons” in March 1938. Critics were enthusiastic, but one commentator writing in La Patrie described the first Fridolinons as comedy “to the point of cruelty” in its depiction of “us.”[32] Mary Travers Bolduc, known to many as “Madame Bolduc” or “La Bolduc” was another singular personality who reflected the life experience of her audience in catchy lyrics sung to the tunes of Irish and French Canadian folk songs. At the peak of her popularity in the late thirties her concerts and records won her both fame and fortune.[33]

During the prohibition era in the United States, Montreal was said to be a “Broadway North”, a town where all kinds of entertainment and alcohol were available. This drew American Theatrical companies, the big bands of the era and Jazz musicians to the city. In 1928, Rufus Rockhead opened his Jazz club Rockhead’s Paradise in the heart of “Little Burgundy,” Montreal’s Black community. It was there that Canadian Jazz musicians like Oscar Peterson were nurtured with clubs like Chez Maurice and the Tic Toc featuring the musicians of the day. Dance music was played at many venues including the upscale Normandy Roof in the downtown Mount Royal Hotel.

Throughout the 1930s roughly a third of the population was able to maintain a reasonable standard of living. Most were skilled or semi-skilled wage earners who, together with their salaried, white-collar counterparts, constituted the middle class. Few of these could escape depression-era anxiety over layoffs or the prospect of being let go, while even those who felt secure dealt with reduced income and reduced expectations. Ambitious, educated men and women in the prime of life spent the decade with little hope of improvements in their standard of living. It was, however, their discretionary income that maintained the concerts, cabarets, movie theatres, dance halls and professional sports contests that added life and colour to the otherwise drab urban scene.

The classical music scene in Montreal was remarkably diverse with regular visits from international groups and lively local productions. Until 1935 the major organisation was the Montreal Orchestra, an English-language company directed by the British-born Dean of Music at McGill Douglas Clark, who had studied with Gustav Holst and Ralph Vaugh Williams. French Canadian music critics complained that Clark, who specialised in the music of Brahms as well as his mentors, ignored modern French and Russian composers. Several wealthy French Canadians, including Athanase David, the province’s cultural minister, persuaded Wilfrid Pelletier, the Associate Director of the Metropolitan Opera in New York, to return to his native city to lead a new orchestra, the Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal. Pelletier developed the OSM and reached out to the community with young people’s concerts and a popular series of free performances at the Chalet atop Mount Royal. Clark’s orchestra continued alongside Pelletier’s until 1941 when it dissolved.[34]

The local theatre scene was centred on the Montreal Repertory Theatre. Created in 1929 through the efforts of Martha Allan, whose family fortune in shipping helped to build an audience for plays performed by a mixture of professional and amateur actors. The MRT produced six plays a season throughout the 1930s and by 1938 listed 2000 subscribers. Martha Allen, who was bilingual and well connected in elite French Canadian and Anglo-Canadian circles, organised a French-language section, MRT Francais, further enriching the city’s cultural mosaic.[35]

Citations

[1] Jean Hamelin, Histoire du Catholicisme québécois Vol III De 1940 à nos jours (Montreal 1984).

[2] Denise Robillard, Georges Gauthier Dictionary of Canadian Biography, (online).

[3] Text of Quadragesimo Anno, (online).

[4] Robillard, Gauthier, (online).

[5] Robillard, Gauthier.

[6] Enrolment peaked in 1928-29 at 159,354 students and declined throughout the 1930s with just 78,452 pupils registered in 1940-41. Quebec Statistical Yearbook 1943, p. 131

[7] Oscar Cole-Arnal “Shaping Young Proletarians into Militant Christians: The Pioneer Phase of the JOC in France and Quebec,” Journal of Contemporary History, Vol 32, 4 (1997), p. 509-526.

[8] La Jeunesse Ouvrière: Journal Jociste available online at the BANQ website. The mass wedding, 23 July 1939 was reported in all daily newspapers.

[9] Hamelin, Histoire du Catholicisme québécois Vol III De 1940 à nos jours.

[10] D. L. Boisvert, “Saint Brother André of Montréal and the Performance of Catholic Masculinity” Studies in Religion/ Science Religieuses Vol 48 (2019) p. 97-114.

[11] Quebec Statistical Yearbook 1943 for all statistics cited below.

[12] F. P. Adam, A History of Christ Church Cathedral (Montreal, 1941) online.

[13] Harold C. Cross, One Hundred Years of Service to Youth (Montreal, 1951).

[14] Both titles are available online.

[15] Roderick MacLeod and Mary Anne Poutanen, A Meeting of the People (Montreal, 2004), p. 195.

[16] Stanley Frost, For The Advancement of Learning Vol II (Montreal 1984), p. 218

[17] Ibid.

[18] Allen Irving, “Leonard Marsh and the McGill Social Science Research Project” Journal of Canadian Studies, Vol 21, No 2, 1986

[19] Allen Irving, “Leonard Marsh and the McGill Social Science Research Project” Journal of Canadian Studies, Vol 21, No 2 (1986): p. 6-25.

[20] Camile Harrigan, Storied Stones of St. Patrick’s Basilica, 1847-2017 (M.A. Thesis, Concordia University, 2018) (online).

[21] Y.C.I. Gadler, The Education of Italians in Montreal (M.A. Thesis, McGill University, 1994) p. 61 (online).

[22] Charles Bayley, The Social Structure of Italian and Ukrainian Immigrant Communities in Montreal 1935-1937 (PhD Thesis, McGill University, 1939) (online).

[23] RCMP Security Bulletin 1937-1940 (online).

[24] Gerald Tulchinsky, “The Third Solitude: A.M. Klein’s Jewish Montreal” Journal of Canadian Studies, Vol 19, 2 (1984).

[25] The Canadian Jewish Chronicle and Canadian Jewish News are available online through the Google News Archive.

[26] Canadian Jewish Chronicle, 29 October 1937.

[27] Canadian Jewish Chronicle, 22 October 1937.

[28] Irving Abella and Harold Troper, None is Too Many, (Toronto, 2023).

[29] Pierre Anctil, “Le Devoir et les Juifs. Complexités d’une relation sans cesse changeante 1940-1936,” Revue internationale d’études québécoises, Vol 18, 2015 (online). Anctil’s body of work argues that antisemitism among French Canadian nationalists and the editors of Le Devoir have been exaggerated but agrees that Pelletier and Omer Héroux expressed such views regularly in the late thirties when the refugee question was debated.

[30] Radios were advertised at $98.00 cash or $4.00 a month for two years.

[31] Richard S. Gruneau and David Whitson, Hockey Night in Canada, (Toronto, 2012).

[32] Wikipedia (French) “Gratien Gélinas” See La Patrie, 19 March 1938.

[33] Wikipedia (French) “Mary Travers Bolduc” See also the film, La Bolduc 2018.

[34] Guylaine Flamand, “Le Montreal Orchestra et la création de la Société des Concerts symphoniques de Montréal (1930 – 1941)”; and Les Cahiers de la Société québécoise de recherche en musique Vol 19, 2018 (online)

[35] P. Booth, “The Montreal Repertory Theatre 1930-1961: A History and Handlist of Productions,” (M.A. Thesis, McGill University, 1989) (online).

One thought on “Chapter II – Mosaic”

Comments are closed.