Montreal’s radio stations and newspapers provided extensive coverage of the war, relying on wire services to supply daily bulletins. Most were credited to Canadian Press (CP) which maintained a bureau in London. CP prided itself on straight reporting without editorialising, but local editors could still shape the story by their use of headlines and leaders at the head of columns. The events of the Battle of Britain, the bombing of British cities in the “Blitz” of 1940-41, were described in considerable detail. News from Berlin and other European capitals were datelined to those cities and readers also had access to syndicated American columnists. Optimistic stories about Royal Air Force (RAF) raids on Germany and the British offensive against Italian forces in Africa were based on official reports. When the war changed direction in 1941, news of the disasters in Greece, Crete and Libya were front page news. Whenever possible, stories about Canadians serving with the RAF or the first RCAF squadrons to reach England were featured, especially if Montrealers were involved.

It was more difficult to find interesting news about the Royal Canadian Navy or the overseas army committed to a static role in the defence of Britain. There was remarkably little comment on the call up of men under the National Resources Mobilization Act (NRMA) even after the training period was extended to four months and conscripts were required to serve until the end of the war. They were, it was understood, to serve only in Canada. The 1941 Victory Loan campaign, which featured a torch with runners moving between towns along the St Lawrence, included Victory Torch rallies in Montreal.

Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union, 21 June 1941, caught everyone by surprise, including the several hundred remaining communist party members in the city. They quickly abandoned their opposition to an imperialist war becoming ardent crusaders in a struggle to save Russia.[1] Anti-communists, almost everyone else in the city, changed their view of Stalin and the Red Army, gradually accepting Russia as a necessary ally.

The invasion of Russia prompted the Imperial Japanese Navy to press for expansion south towards the oilfields of the Dutch East Indies. The first move was expanding their protectorate in French Indochina—the north of which had been invaded and occupied in September 1940—to the entirety of the French colonial holding. The United States responded with a freeze of Japanese assets and a trade embargo that included oil. Britain, the Netherlands and the Commonwealth followed the American lead. A Japanese ship, scheduled to load Canadian grain was forced to leave Vancouver without a cargo.[2] The American Chiefs of Staff had decided that if Japan was to be deterred from further aggression efforts to strengthen defences in the Pacific, particularly the Philippines, was urgent. The recall of retired General Douglas MacArthur and his appointment as commander of both Philippine and American forces was announced with great fanfare. Reinforcements and B-17 “Flying Fortress” bombers were soon on their way. The visit of two USN heavy cruisers to Australia was front page news in Montreal, alongside a story “Singapore strongly reinforced”.[3]

By late August, these efforts seemed to have paid off as the Japanese were asking for further discussions with the Americans. Churchill dealt with Australian pressure to return their divisions in North Africa, sending a “Secret and Personal” message to the Australian Prime Minister which sought retention of the units, noting that, “events about Japan have taken a more favourable form in the last month and I cannot believe that the Japanese will face the encounter now developing around them.”[4] In Canada, the public mood in English-speaking Canada, as interpreted and shaped by the daily press, was soured by the German victories in Russia and the continuing inactivity of the Canadian Army. Mackenzie King was pressured to send a telegram to Churchill “reaffirming the government’s willingness to have Canadians serve in any theatre”. There was, however, a high proportion of Commonwealth troops in North Africa, the only active front, so the Canadians would have to stay put.

Canada’s marginal involvement in military operations helps to explain the reaction of cabinet ministers to the sudden request to send “one or two“ battalions from Canada to reinforce Hong Kong, an action the British Chiefs of Staff believed would “increase strength out of all proportion to actual numbers involved and would provide a strong stimulus to garrison and colony, it would further have a great moral effect in the whole of the Far East and would reassure Chiang Kai Shek as to the reality of our intention to hold the island.”[5]

The Acting Minister of Defence, L. G. Power’s immediate reaction was positive. “It struck me”, he recalled, “as being the only thing we could do.” No final decision could be made until J. L. Ralston, the Minister, returned, but Power contacted the Chief of the General Staff, Major General Crerar, who had studied the problem of defending Hong Kong while a student at the Imperial Defence College. Crerar had also discussed the issue earlier in the summer, when he and Ralston met with MajorGeneral A. E. Grasset, who had just retired as Commander in Chief of British troops in China. They had agreed that in the event of war, the best a garrison could do was to hold out until relief arrived in the form of a British or American fleet. When Ralston returned from the United States, he supported the British request as did the Prime Minister and the Cabinet. For security reasons none of this reached parliament or the public until “Force C,” a brigade headquarters and two infantry battalions, reached Hong Kong on 16 November.[6]

The next day, the Prime Minister announced their safe arrival in a brief statement that described the action, “as associating Canadian troops with those of other forces of the British Commonwealth in defence against aggression actual or threatened.” The editor of the Montreal Star applauded the government’s initiative, declaring that “all Canadians will be thrilled with the news.” The Gazette, which rarely agreed with anything the government did, was equally effusive as was the English-language press in the rest of the country. Le Canada took a different approach describing the expedition as “a gesture of solidarity with the British Empire.” Le Devoir reminded readers of Henri Bourassa’s warnings about the danger of Canadian involvement in the Empire’s wars, during the naval debates of 1911.[7] Canadians soon learned that “Force C” included battalions from the Winnipeg Grenadiers and the Royal Rifles, a Quebec City, English-language regiment.

The problem of sending inexperienced, semi-trained battalions to Hong Kong was to figure largely in the criticism directed at the government and army in the aftermath of the royal Commission appointed to review the decisions made about Hong Kong.[8] It therefore seems worth noting that when battalions in 4th Division were considered for the expedition, a Montreal unit, the Grenadier Guards, was a prime candidate. The battalion, which later converted to an armoured regiment, may have shown great promise in September 1941, but at that point it was less well trained than the Royal Rifles which had been mobilised much earlier.[9]

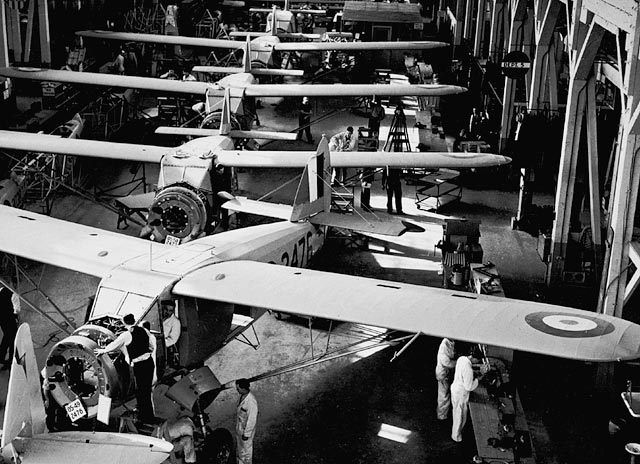

Canada’s most important contribution to the Allied war effort in 1941 was the rapid expansion of the British Commonwealth Air Training plan. For the Montreal region, this meant that further growth of Number 1 Wireless School and the creation of #13 Service Flying Training school for pilots at RCAF station Saint Hubert.[10] A more important consequence was the impact of the plan on the region’s aircraft industry. Three of Canada’s major aviation companies, Canadian Vickers, Fairchild Canada and Noorduyn were located on the edge of the city. Together, they employed less than 1,000 workers in 1939. But in the 1941 census, 7,714 employees were working in the industry, making it the city’s third largest manufacturing employer. That number soon doubled, placing aircraft production on a par with the garment industry in Montreal.

War orders led to plant expansion, a search for skilled labour and the growth of industrial unionism. Montreal had long been a center of activity for the International Association of Machinists (IAM), two railway lodges and four additional skilled trade locals were well established in the city. The American Federation of Labor had granted the IAM jurisdiction for the aircraft industry in the United States, where the union was in conflict with the United Automobile workers of the CIO. There was no UAW presence in Montreal, so when the IAM chartered a single local, 712, to organize the entire industry, there was no competition. Robert Haddow, an experienced organizer, was appointed business agent in November of 1939, and by the spring of 1940 an extensive organizing drive was underway. Initially, the major companies were unwilling to negotiate, and the Union appealed to the Federal Department of Labour for the appointment of a board of inquiry under the Industrial Disputes Investigation Act. After presentation of the union’s case, Canadian Car and Foundry managers, who had won subcontracts for airplane parts, agreed to immediate negotiations, reaching a settlement before the board reported. A similar contract was then signed with Canadian Vickers, and early in 1941 with Noorduyn, Fairchild and the Federal Aviation Company. All of this was accomplished without a strike or representation vote. Indeed, it was not clear that lodge 712 had enrolled a majority of aircraft workers when it was recognized as the sole bargaining agent. Since there was no wage control order in effect when the first agreement was signed, wage rates were set across the industry at fifty cents an hour for unskilled production workers, sixty cents for semi-skilled and seventy-five cents for journeymen, roughly thirty percent above those in comparable occupations.[11]

Shipbuilding, a long-established industry in Montreal, began to expand in 1940 when Ottawa agreed to contracts for sixty-four anti-submarine whaling vessels, which Winston Churchill decided to call Corvettes. Canadian Vickers built eight of the first Corvettes, enough to add hundreds of workers.[12] When a program to build dry cargo vessels began in early 1942, Vickers contracted for six, 10,000-ton ships. A new yard, owned by the Dominion Government but managed by local engineering companies, built twenty-two of the ships, raising local employment in the industry to 12,000 employees. The existence of well-established craft unions determined to protect and advance the prospects of highly skilled labour, limited the unionization of the new semi-skilled workers. Montreal’s shipyards largely avoided the labour conflict that plagued the lower St Lawrence companies by paying premium wages.[13]

Armoured Fighting Vehicles, especially the British-designed Valentine tank, became an important part of Montreal’s contribution to the Allied war effort. The Canadian Pacific Railway’s Angus shops received an order for 300 Valentines in June 1940 and eventually 1300 were produced. Almost all were sent to the Soviet Union as part of the American Lend-Lease program. A Canadian version of the American M3, the Ram, was manufactured by the Montreal Locomotive works using engines and transmissions imported from the United States. Unionization was limited to skilled trades, but competition for workers forced companies to raise all wages.[14]

The war transformed the city’s other industries.[15] Demand for military uniforms allowed the Amalgamated Clothing Workers to achieve a ten percent increase with the briefest of strikes. The International Ladies Garment Workers union initially lacked such leverage, but in April 1940 a mass walkout involving 5,000 workers led to a new agreement that included a union shop, the forty-four-hour week, wage increases, and time-and-a-half pay for overtime, limited to eight hours a week. It was this strike, not the more famous 1937 battle, which established the ILGWU in Montreal. These and other wage increases led the government to develop an early attempt at wage control. On 16 December 1940, the cabinet used its powers under the War Measures Act to pass an order in council (PC 7440) which had the force of law.

PC 7440 instructed boards of conciliation established for war industries, to freeze wages at their 1926–1929 level, or any higher level since established, unless it can be clearly shown that when such level was established, “wages were depressed and subnormal or unduly enhanced.” Boards were permitted to authorize, but not order, a cost-of-living bonus to be paid as a flat amount per week, uniform to all workers as the rise in the cost-of-living falls without distinction on all classes. Early in 1941 the Minister of Labor declared that for every five percent increase in the cost of living, a maximum bonus of $1.25 might be allowed. The first major test of the revised wage control order occurred at Montreal’s Peck Rolling Mills, a subsidiary of the Dominion Steel and Coal Company or Dosco. The Steel Workers organizing committee SWOC local 2174 was able to sign the large majority of the 350 employees at Peck and bargain successfully for an agreement on union recognition, a five-day, fifty-hour work week, and time-and-a-half pay for overtime. Dosco refused a general wage increase. The conciliation board decided that since the 1926–29 wage level had been lower than the current $16.45 a week, no increase was justified. The board rejected the relevance of the union’s argument that Dosco workers in Sydney and Trenton, and steel workers in other areas, were paid at higher rates and insisted that it is difficult to see how the fairness and reasonableness of wage scales can be determined by other than local standards.

The Minority Report, written by labour lawyer Jacob Cohen, contained a biting critique of his colleagues’ views. He argued that “if this strict legalistic interpretation of PC 7440 was to be followed conciliation boards could be replaced by an official of the accounting staff of the department.” He stated that he could not accept the interpretation offered by the majority, and noted it is nowhere seriously suggested that the cost of living in Montreal justifies a lower wage rate. Beyond this, I am unable to understand, much less agree with, the concept of variation in our social and economic standards. I know of no principle which justifies the proposition that any group of people of any province or of any industry are mere stepchildren in the Canadian social order and can be expected to be satisfied with a lower standard of living.” Cohen went on to propose an increase to forty cents an hour, plus the cost-of-living bonus. The company, backed by the majority report, stuck to existing wage scales. Employees went out on strike on 23 April 1941, and stayed out until 11 June when the Dominion government offered to reconvene the conciliation board. The board failed to meet during the summer, and the dispute ended with the temporary collapse of local 2174.

The Department of Labour was swamped with requests for conciliation boards throughout the rest of 1941 and generally tried to follow what became known as the Peck Rolling Mills formula. However, in a growing number of cases the commissioners withdrew when settlements were reached, even when the agreements clearly violated wage control principles. The government’s policy was a shambles because during 1941, Canada crossed the threshold from a labour surplus, to one of growing labour shortages. Wage settlements in manufacturing had resulted in a fifteen percent increase in rates; this figure was in no way indicative of increases in earned income, as full employment and extensive overtime resulted in a much more dramatic rise in take-home pay.[16]

After ten years of massive unemployment, full time work, with increasing wages transformed the mood in the city. The rise in food prices and rents affected lower income families, but 1941 prices and rents were still below the 1929 figures, and little in the way of shortages or rationing had appeared. Nevertheless, the government feared that an inflationary pattern, similar to the one experienced during the first two years of the Great War, was emerging. The Wartime Prices and Trades Board, established in 1939, had limited its intervention to specific commodities, but now order-in-council PC 8258 set a ceiling for all prices and services based on the highest price paid between 15 September and 11 October 1941. A fine of up to $5000 and two years in prison was provided for failure to enforce the measure. Rental costs were also frozen in a separate order. Price control gave rise to a considerable black market but was otherwise remarkably successful. Wage control proved to be far more difficult to manage. A new administrative mechanism was established in November 1941, a National Labour Board and nine regional boards, which were to grant wage increases only if it could be proven that wages were low in comparison with “substantially similar occupations.” The cost-of-living bonus was made compulsory, but the methods of calculation were so complex conciliation boards accepted employer requests to raise wages in the face of intense competition for workers. Boards were also authorized to use their own judgment in determining the cost-of-living bonuses. Throughout 1942, while the government claimed to be preventing or limiting wage increases, weekly rates increased by ten to fourteen percent, and incomes, due to overtime and labour force shifts into higher paying occupations, by much more.[17] The help wanted ads in La Presse and the Star illustrate the demand for men and women in a variety of occupations. Young girls were sought after for the needle trades, as were boys over fourteen with bicycles.

Throughout 1941 and 1942, the Federal Cabinet devoted considerable time to what was described as a manpower crisis due to the demands of the armed services, especially what some called “the Big Army.” The anxiety expressed by both politicians and civil servants was genuine but so too was their belief that they were able to control and direct a complex economy with rules issued by order-in-council. On 27 March 1942, in the midst of a deeply divisive plebiscite campaign, the Prime Minister announced a plan to enforce a National Selective Service (NSS) system. The NSS would forbid men between the ages of seventeen and forty-five from taking jobs in non-essential industries; there would also be measures to encourage more women to seek employment in war industries. Orders-in-council to advance these aims would be passed as required but the government hoped for cooperation without coercion. The NSS was to channel men into essential industrial jobs or compulsory service for home defence. Elliott Little, a Montreal businessman who was appointed director of the NSS, believed the government was serious about regulating the economy. He resigned in November 1942 explaining that in the absence of a clear directive, manpower policy suffered from ambiguous and divided authority which had led “from confusion to friction, to obstruction. The result has been a virtual paralysis in the national selective service organization.”[18]

Historian Michael Stevenson reinforces this assessment in his book Canada’s Greatest Wartime Muddle: National Selective Service and the Mobilization of Human Resources During World War II. Stevenson’s case studies reveal a level of internal conflict and regional autonomy that made any comprehensive scheme impossible.[19] A post-war study of Canada’s use of its labour force notes that far fewer Canadians were directly involved in the war effort than in the United Kingdom or the United States: 22% were in the armed forces in the UK, 18.5 % in the USA, but only 14.4 % in Canada. Civilian war employment accounted for 33% of the labour force in the UK, 21% in the United States and only 12.6% in Canada. Consumer goods and services increased by 35% during the war years when the Canadian population increased by only about 6%.[20]

The perception of a manpower crisis led the men who directed the Canadian war effort to accept the idea of enlisting women in the three services. When the RAF announced that uniformed members of the women’s auxiliary of the RAF would be posted to air training schools in Canada, the RCAF moved quickly to establish a women’s division, the WDs. Women in the RCAF held the same rank as men and were subject to the same chain of command. Female officers and NCOs issued orders to men as well as women. They were not permitted in combat and therefore were excluded from aircrew, but everything else was open to them, and by 1944 WDs were employed in 65 of the 102 RCAF trade categories. Despite the best efforts of the senior personnel officer, Air Marshall J. A. Scully, who argued for equal pay for the WDs, the war cabinet stuck to salaries at eighty percent of men’s entitlement.

Few of the 17,000 women who served in the WDS were French Canadians. The air force operated entirely in English, required junior matriculation for officers, and failed to offer a pre-basic training English-language courses until late in the war. Women from Montreal’s Anglo-Celtic and Jewish communities were, like their male counterparts, anxious to serve in Air Force blue and enlisted in large numbers. The Royal Canadian Navy waited until 1942 to recruit women directly into the navy. Initially, the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service, or WRENS, were clerks, cooks, stewards, and stenographers but soon had access to jobs as plotters, coders, telegraphists, and other operational postings. The Navy recruited 6,718 women, 1,000 of whom served outside Canada.[21]

At home, the WRENS were perhaps best known for their part in “Meet the Navy,” the most professional and popular review produced by any of the three services. The show, with its hit song “You’ll Get Used to It”, played to half a million Canadians before going overseas where it became one of the great hits of 1945’s London season.[22] As with the Air Force, English was the language of instruction and communication.

The army approached the prospect of including women with much hesitation. Originally, National Defence headquarters, which employed 1,325 civilian women, hoped they would join the Canadian women’s army corps or CWACs, providing most of the 1,500 women the army thought were required in 1941. By March 1942, as voluntary recruitment of men declined, the target was raised to 5,000, so that A-category men could be released for overseas service. When women proved to be of great value, they were taken directly into the army rather than an auxiliary service and a vigorous recruiting campaign began. By July 1943, 70,000 thousand women had visited a recruiting office, but just 37,000 agreed to be medically examined, and only 28,000 were accepted. While recruiting ads were placed in French-language newspapers, no provision for English-language training was made until 1944, and no French-language units were created. The CWAC officer training school at Saint Anne de Bellevue, on the western edge of Montreal, functioned entirely in English. At the end of the war, 11,706 CWACs were serving in Canada and 853 in Britain. Almost all served as a clerk, stenographer, or kitchen and laundry worker which may account for the drop-out rate, and the general view that joining the army was not really performing a vital war service.[23]

Montreal’s political scene was remarkably calm during 1941, but in Ontario and parts of Western Canada conscription for overseas service as part of a total war effort gradually became a major issue. This was especially the case in Toronto, where the Globe and Mail and Telegram led the charge. The Montreal Gazette, voice of the Conservative Party in the city, joined in the agitation for conscription and a so-called national government, while the Star, Herald and mass circulation French-language papers maintained support for the Liberals. Le Devoir, hoping to arouse public opinion, regularly quoted the Gazette and other conservative newspapers condemning their “ultra-loyalist” sympathies.

The editors of Le Devoir also engaged in a running battle with Jean-Charles Harvey and his weekly Le Jour, which was not only pro-participation, but pro-De Gaulle and anti-Vichy. Harvey’s commitment to compulsory education and better instruction in English were added reasons for Le Devoir to refer to Harvey as “John Charles McHarvey.” Le Jour replied with bitter attacks on the nationalists, claiming that Le Devoir published more war news from Berlin and Rome than London. Then, in November, Le Jour published an expose of L’orde Jacques Cartier with a headline reading “Le Ku Klux Klan du Canada Francais.” The article described the OJC as a secret society of sectarian nationalists, vichyards, and antisemites, and listed prominent members.[24]

Le Canada, the Liberal Party newspaper, was also critical of Le Jour as an advocate of a total war effort. The editor Eustache Letallier de St. Just, echoed and amplified the limited-participation, pro-Vichy views of Lapointe and Cardin. When Louis Francoeur was killed in a car accident, the head of Radio Canada Louis Frigon, who shared these views, selected St Just to replace Francoeur.[25] St. Just’s program “La guerre et nous” presented a very different perspective on the war. The scripts were printed in Le Canada alongside signed editorials attacking those who favoured a more robust war effort. St. Just was especially critical of the Gazette and its Washington correspondent, Lionel Shapiro, who he said, “lacked discretion, like others of his race”.[26] He questioned Shapiro’s failure to enlist (Shapiro was forty-one years old) drawing a furious response from A.M. Klein, the editor of the Canadian Jewish Chronicle.[27] K. Sandwell, the editor of the Toronto weekly Saturday Night, took note of St. Just’s editorials in a column titled, “The Veto Power of Quebec”. St. Just ignored Klein and dismissed Sandwell’s comments, continuing to argue the case for a limited war effort claiming that those who advocated total war were inviting internal conflict which would discourage voluntary enlistment.[28]

The death of Ernest Lapointe, 26 November 1941, eclipsed all other news in Quebec. Lapointe had been the dominant political force in Quebec since the 1920s and references to a King-Lapointe government were common in the province. Lapointe had expressed regret for his role in supporting appeasement, but he never changed his views on limited participation and conscription.[29] Lapointe’s death was in turn eclipsed by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour and Hitler’s declaration of war against the United States. America was no longer neutral and soon seemed to be reeling from a series of catastrophic battles in the Philippines. British defeats at sea and in Malaya/Singapore also had a powerful impact on attitudes towards the war. Specific news about the Japanese assault on Hong Kong did not become available until 23 December when Ralston announced that “there had been very heavy casualties including the death of the force commander Brigadier JK Lawson.” Canadian Press dispatches described a stubborn fight that was still underway on 24 December, but the next day Hong Kong surrendered.[30] The Montreal Star carried a photograph of two Montrealers serving with the Royal Rifles, and news of the reaction in Quebec City, where Archdeacon F. G. Scott, the former Great War Padre of the Canadian Corps, recited his poem “Hymn in Time of War” at a special prayer service for the regions’ protestants. Montreal’s Archbishop called for special prayers for Canadians in all services and especially for Quebec troops in Hong Kong.[31]

Newspapers in Montreal largely accepted official accounts of the Canadian role in the defence of Hong Kong even after the list of casualties and prisoners of war were released. Le Canada printed, in English, an editorial from the Vancouver Sun which raised the key questions:

heroism however inspiring cannot alone win battles it takes generalship and united command. Canadians will wish to know that this was shown at Hong Kong because Hong Kong was partly our show. Did the Dominion government understand the military implications when it sent Canadian troops there? Did Ottawa believe, on the advice of its military advisors, that Hong Kong was a bastion or was the Garrison considered a sacrifice from the start. These questions will be asked in parliament so they might as well be asked here. There have been too many gallant rear guard actions.[32]

There was however no immediate follow up, and for a brief period Montrealers came together mourning those lost in the battle.

Deep divisions over the purpose of the war reemerged over the occupation of the Islands of St Pierre and Miquelon by a Free French naval flotilla on Christmas Eve. French and English-speaking Canadians had maintained their very different attitudes towards Vichy France since June of 1940. The government’s continued recognition of Pétain’s regime angered those who believed that Pétain and Pierre Laval were pro-Nazi collaborators, assuming that Ottawa allowed Vichy officials to freely spread propaganda out of deference to French Canada, where opinion varied from neutrality to outright support of Pétain. Few knew that the British government had asked Canada to maintain diplomatic relations and the Prime Minister, aware of the views of Lapointe and Arthur Cardin, was happy to oblige.

On Christmas Eve, a Free French naval force sailed from Halifax after informing Canadian authorities that they were to engage in an exercise. De Gaulle had in fact authorized Admiral Emile Muselier to seize the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon which they captured without bloodshed. The American state department was bitterly opposed to De Gaulle and demanded a restoration of the islands to Vichy sovereignty. When a vote by the adult male population of the islands endorsed the takeover with near unanimity, there was little Washington or Ottawa could do without looking even more foolish.[33] In Montreal, the Gaullist coup became front page news with Le Devoir and Le Canada expressing outrage at the actions of Jean Charles Harvey and his French-born war correspondent, Jean Le Bret, who were said to be involved in the plot. Le Jour published Le Bret’s account of the exercise which he had joined, further annoying the pro-Vichy press.[34] The Mayor of Montreal was also provoked by the incident when a fundraising rally for the work of the Red Cross in the Soviet Union was advertised as a celebration of the liberation of the islands. He declared that the rally organizers were “promoting disharmony” but the event went ahead as planned.[35]

On 29 December, Churchill who had travelled to Washington to co-ordinate future strategy with Roosevelt made a short, memorable visit to Ottawa. Large crowds filled the streets to cheer the man who had become English Canada’s inspirational leader. Churchill’s speech to parliament, broadcast nationally on the CBC and Radio Canada included his comment on predictions that after the fall of France, Britain would have its neck wrung like a chicken. After a pause he quipped “some chicken some neck” to wild applause. Churchill went on in a more sombre note warning that “not only great dangers, but many more misfortunes, many shortcomings, many mistakes, many disappointments will surely be our lot … death and sorrow will be the companions of our journey, hardship our garment, constancy and valour our only shield.”

Lapointe’s death shifted the balance of power in the Dominion cabinet allowing members who were “tired of listening to Quebecers say conscription was impossible” to press their case. They reluctantly accepted the prime minister’s decision to announce a plebiscite asking Canadians to release the government from its pledge to restrict conscription to service in Canada. J. L. Ralston, the leading conscriptionist, told Grant Dexter that the purpose of conscription was to get more men for the army from the English-speaking provinces. The army, he said, “could not use masses of French Canadians who could not speak English, though it was impossible to say this in public.” He assumed that a yes vote in the plebiscite would allow the army to draw upon the best trained NRMA recruits.[36] The plebiscite, scheduled for 27 April 1942, drew strong reaction from the city’s newspapers. The Star, which had generally supported the government, criticized the decision in a scathing editorial, accusing King of avoiding responsibility. Changes in the war situation since the passage of the NRMA demanded new policies and leadership, the paper argued, and that “a plebiscite is not leadership.” The Gazette, which had long supported conscription and a total war effort, was predictably outraged. Despite this tempest, all the English-language newspapers were soon committed to the Yes campaign.

Nationalist opposition was a given, and Le Devoir insisted that the 1939 compromise of no conscription for overseas service was a contract with Quebec, not the rest of Canada, and must not be broken. Le Canada, the voice of the Liberal Party in Montreal, argued against conscription citing Lapointe’s pledge. All of this proved to be too much for the Liberal Party, and in March 1942 St. Just was replaced by Edmond Turcotte who moved quickly to moderate the paper’s position and endorse a yes vote. Turcotte, a Liberal in the rouge tradition, had been Le Canada‘s editor until 1937, when his support for the Spanish republican cause led to his dismissal and the appointment of St. Just.[37]

Turcotte found there was little he could do to turn the tide of public opinion in French Canada where a broadly based opposition to conscription had been nurtured by the Liberals for two decades. The newly formed Ligue pour la defense du Canada, led by the independent MP, Maxime Raymond, and the editor of Le Devoir, Georges Pelletier, won the support of Catholic labour, farmer organizations, and the prestigious St-Jean Baptiste Society. The Ligue mobilised hundreds of young French Canadians to campaign for a no vote, drawing upon the Jocistes as well as university and classical college students. When Radio Canada refused free time for broadcasts on the grounds that the Ligue was not a political party, funds were raised to use the private radio stations by selling memberships at one dollar. This also helped to pay for newspapers ads and pamphlets. A mass meeting at St James market featured the return of Henri Bourassa to centre stage and a post rally riot that led to eighteen arrests and eight injured policemen.[38] The next morning, 12 February, the streets in sections of the city were littered with broken glass from store windows and streetcars. The Star described the events of the night as a “Storm in a teacup” and a “baby riot”, an attitude adopted by the French-language press.

As the day of the plebiscite approached, Liberals made last minute attempts to increase support for a yes vote by arguing that King could be trusted to avoid sending conscripts overseas. Arthur Cardin was persuaded to speak out and the newly elected Minister of Justice, Louis St Laurent, told French Canadians that “they cannot have things in this war the way they want them. They must be prepared, to make sacrifices in the interest of national unity.”[39] The Prime Minister and Premier Godbout tried to persuade French Canadians that the issue in the plebiscite was not conscription, but simply a release from a previous pledge, and they should trust the government. Georges Vanier, the Great War hero of the 22nd Battalion, then serving as the officer commanding the Quebec City military district, urged a yes vote because “if we vote no, our fine war effort will no longer impress the other provinces and the United States.”[40] No influential French Canadian tried to argue that isolating themselves from the human tragedy unfolding beyond their borders was immoral. In a war against Hitler, French Canada preferred to see itself as the victim of Anglo-Canadian imperialism.

The results of the vote demonstrated the sharp division along linguistic-cultural lines with seventy-two percent of Quebec voters registering a no, while seventy-nine percent voted yes in the other provinces. The margin in Montreal was much less, with just over fifty percent voting no (248,665 vs. 240,851) indicating that a significant number of French Canadians in the city trusted Mackenzie King or were committed to the Canadian war effort.[41]

Newspaper reaction divided along predictable lines. The Gazette condemned the “self isolation” of Quebec and declared that French Canadians had “voted themselves out of the company of Allied nations”. La Presse, determined to avoid controversy, argued that Quebec “had full confidence in the Prime Minister but wanted to be “respected for its anti-conscriptionist stance”. La Patrie, now edited by Letellier de St. Just, claimed that the divergent opinions would lead King “to exhaust every possible source of voluntary enlistment before resorting to obligatory overseas service” and urged everyone to stay united despite differences over conscription. Le Devoir and the Ligue insisted that the national vote “in no way relieves the government of its anti-conscriptionist promises to the province of Quebec.”[42]

The conscriptionist Liberals persuaded the very reluctant prime minister that immediate legislation was required to amend the NRMA, cancelling the clause limiting compulsory service to Canada. This set off a new controversy that led to Cardin’s resignation from the cabinet. Cardin’s speech on the passage of Bill 80 reflected his deeply held views on conscription and the war. He told the House that “the majority should pause before applying the iron heel to the minority in this country. When you are hurt in the soul it is much more difficult to heal than when you are hurt in the body. Exercise your authority, you in the majority, but with kindness.” A large majority of the Quebec caucus, agreeing with Cardin voted against Bill 80.

Louis St Laurent, newly elected in Laurier and Lapointe’s riding of Quebec East, maintained cabinet solidarity and voted for the Bill. St Laurent told Grant Dexter, that:

… the best way of dealing with his caucus was not to criticize or condemn them but to try and understand their position. They are not in the main against the war. They want to win and do their part… Most of the members had been opposed to conscription and had given pledges…their electors had not released them. They felt they were bound by the no vote. All of them firmly desire the government to stay in office.

St Laurent also claimed that with Cardin gone, a real war-morale campaign could begin in Quebec; “defeatist or anti-war propaganda will be ruthlessly dealt with. Georges Pelletier will be called on the carpet and asked to change his tune or Le Devoir will be suppressed.”[43]

Despite St Laurent’s brave words, little changed in Le Devoir or elsewhere. More than 300 Quebec municipalities passed a resolution, prepared by the Ligue, denouncing conscription, and the Quebec Legislature voted sixty-one to seven to condemn the measure. On 19 May large crowds again gathered at the Marche St. Jacques to hear Maxime Raymond, Paul Gouin and Rene Chaloult urge renewed opposition to conscription. Chaloult, a member of the provincial legislature, crossed some imaginary line in his denunciation of the British Empire and was charged under the Defence of Canada regulations, charges that were later dismissed on freedom of speech grounds.[44]

For some Montrealers fear of a German victory rather than conscription was the most important issue, and the prospect of a renewed Nazi offensive in Russia was a constant theme in the press. Local communists and liberal-left activists joined the international push for a “second front” to relieve pressure on the Soviet Union. On the same night nationalists gathered to celebrate their victory in the plebiscite, the “Quebec Committee for an Allied Victory” sponsored a rally at the Montreal Forum. Speeches from various local leaders, including McGill professor Raymond Boyer, were interspersed with performances by the newly formed Montreal Negro Theatre Choir, the popular French Canadian “Alouette Vocal Quartet”, and Paul Robson, the great American baritone who sang “Joe Hill” and other union ballads as well as “Old Man River”. Robson’s presence apparently accounted for the size of the crowd which packed the forum as later attempts to hold “Second Front” meetings attracted far smaller crowds.[45]

Ontario Conservative party leader George Drew’s biting criticism of the government’s organization of the Hong Kong expedition led the prime minister to appoint a one-man Royal Commission to investigate the charges. Chief Justice Lyman Duff, who had reluctantly accepted the position, released a report in June which largely exonerated the government, drawing bitter commentary from Drew and the Tory press. The Gazette and, to a limited extent, the Star joined in the attacks on Duff’s credibility but when the government postponed parliamentary debate on the Royal Commission until the last days of the session in late July, the issue faded from view, at least in Montreal. Yet another aspect of public opinion was evident during Army Week, 29 June to 5 July. All the dailies except Le Devoir provided free publicity for a series of events celebrating the army. La Presse went overboard with a twelve-page special section in its Saturday edition, 27 June. Feature stories about French Canadian regiments, military heroes and current officers serving as French-language instructors were featured. Neither the plebiscite nor conscription was mentioned.

Citations

[1] RCMP Security Bulletin 1941

[2] David K Francoeur, “Fuelling a War Machine: Canadian Foreign Policy in the Sino-Japanese War 1937-1945,” (MA Thesis, Queens University, 2011)

[3] Montreal Gazette, 1 August 1941.

[4] George Hyland, War in the Pacific: A Chronology January 1 ,1941 through 30 September 1945 (UNT Digital Library, 2014)

[5] Terry Copp, “The Decision to Defend Hong Kong, September 1941” Canadian Military History, Vol. 20, No. 2 (2011)

[6] Paul Dickson “Crerar and the Decision to Defend Hong Kong” Canadian Military History, Vol. 3, No. 1 (1984).

[7] Le Devoir, 17 & 18 November 1941.

[8] Lyman Diff, Report on the Canadian Expeditionary Force to the Crown Colony of Hong Kong (Ottawa 1942).

[9] Patterson, Soldiers of the Queen, p. 212.

[10] See RCAF Station St. Hubert, RCAF Info.

[11] Terry Copp, “Rise of Industrial Unions,” Relations Industrielles / Industrial Relations, 37, 4, (1982): 843-875.

[12] See, https://www.silverhawkauthor.com/subcategories/royal-canadian-navy-rcn

[13] James A Pritchard, A Bridge of Ships: Canadian Shipbuilders During the Second World War (Montreal 2011).

[14] Tank Production in Canada, AHQ Report No. 38 (1950).

[15] The following paragraphs are from, Copp, “Industrial Unionism.”

[16] The average weekly income of all earners rose from $19.71 in May 1941 to $25.73 in September 1941. Labour Gazette October 1941.

[17] K W Taylor, “Canada’s Wartime Price control 1941-1946,” Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science, Vol 13 No 1 (1947): 81 – 98.

[18] CP Stacey, Arms Men and Government, p. 404.

[19] Michael Stevenson, Canada’s Greatest Wartime Muddle: National Selective Service (Montreal 2011)

[20] E L M Burns, Manpower In the Canadian Army 1935-1945, (Toronto 1956).

[21] Terry Copp, “Servicewomen of World War II” Legion Magazine, 1996.

[22] Bonar A Gow, “The Meet the Navy Show” militaryandnavalmuseum.org.

[23] J N Buchanan, The Canadian Women’s Army Corps 1941-1946, AHQ Report No. 15 (1947) .

[24] Le Jour, 15 November 1941.

[25] Paul Coture,”Vichy-Free France Propaganda War in Quebec 1940-1942,” Historical Papers / Communications Historiques, 13, 1 (1978): 200-216.

[26] Le Canada, 19 November 1941.

[27] Canadian Jewish Chronicle, 29 November 1941.

[28] Le Canada, 29 November 1941.

[29] Gibson and Robertson, Grant Dexter, p. 81-82.

[30] La Presse and The Star provided detail.

[31] Montreal Star, 30 December 1941.

[32] Le Canada, 4 January 1942.

[33] Martin Thomas, “Deferring to Vichy in the Western Hemisphere: The St Pierre and Micquelon Affair of 1941” International History Review 19, 4 (1997): 809-835.

[34] Le Jour, 3 January 1942.

[35] Montreal Star, 4 January 1942.

[36] Gibson and Robertson, Grant Dexter, p. 232.

[37] Marie-Eve Tanguay, “La Pensee de Edmond Turcotte,” (MA Thesis, Universite de Montreal, 2007)

[38] Laurendeau, Witness for Quebec.

[39] Gibson and Robertson, Grant Dexter, p. 267.

[40] Le Canada, 10 February 1942.

[41] Le Canada, 24 April 1942.

[42] Le Devoir, 24 April 1942.

[43] Gibson and Robertson, Grant Dexter, p. 321-322.

[44] Le Devoir, 19 – 21 May 1942.

[45] Montreal Star, 20 May 1942.

One thought on “Chapter V: Distant War”

Comments are closed.