The Canadian Government was neither consulted nor informed about the Anglo-American debate over the best strategy for the Allies to pursue in 1942. The American Chief of Staff, George C. Marshall, sought to build up American forces in England in preparation for an invasion of France in 1943, code named “Operation Roundup.” This was to be preceded by accelerating the combined bomber offensive and raids on the enemy-held coast to harass the defenders and give experience to Allied troops. The British Chiefs of Staff seemed to agree but then joined Churchill in his campaign to persuade Roosevelt that the invasion of French North Africa should take place in 1942. Marshall warned Roosevelt that this diversion would jeopardize plans for 1943 but the president, with his eyes on the 1942 congressional elections, wanted Americans in action in the European theatre as soon as possible.

Preparations for Operation Torch, as the North African venture was to be called, ought to have ended further preparations for raids on the coast of France but Combined Operations Headquarters, COHQ, under Lord Louis Mountbatten, continued to plan a major raid on Dieppe which would test equipment and interservice cooperation. COHQ believed that much could be learned in a large scale assault against the kind of port city that everyone assumed would be a necessary objective in an actual invasion. The challenge was to develop an operational plan that could accomplish reasonable goals and minimize casualties. Dieppe was selected as the target because it was thought to be lightly defended and was in range of fighter-aircraft based in England.

The plan for “Operation Rutter” as the raid was originally named certainly provided the opportunity to practice a joint and combined operation with the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force, and to test landing craft and the new Churchill tanks under combat conditions, but little attention was paid to limiting casualties or setting reasonable objectives. Rutter, which was to take place in July 1942, involved frontal attacks on defences of unknown strength with very limited fire support. The Admiralty, shocked by the success of Japanese land-based aircraft in sinking the battleships Prince of Wales and Repulse, refused to allocate heavy cruisers, never mind battleships to Rutter so naval fire would be limited to four-inch guns of six destroyers. The RAF was keen to participate, hoping the raid would provoke the Luftwaffe into the kind of battle Fighter Command had been seeking. Support for ground troops had never been an RAF priority and once the use of heavy bombers was ruled out all that was left was two squadrons of Hurricane fighters carrying four 250-pound bombs. Additional Hurricane fighters with cannons and some medium bombers were also available while RAF Spitfires provided air cover.

General Bernard Montgomery selected 2nd Canadian Infantry Division as the troops best suited for Rutter declaring that: “there were good prospects of success if weather conditions were favorable; the Navy puts us ashore roughly in the right places at the right times and we have average luck.” He added “the Canadians are first class chaps if anyone can do it they can.”[1]

How could professional soldiers, British and Canadian, have allowed such a flawed scheme to go forward? The reality is that in 1942 senior Allied officers held totally unrealistic ideas about the kind of fire support required to attack prepared defences. As C. P. Stacey, the Canadian official historian has noted all Allied plans for operations in 1942 emphasised the shock effects of tanks, speed, surprise and air cover as the keys to success The Great War artillery-based battle doctrine that was reemerging in North Africa had little impact in Britain where generals, including Bernard Montgomery, were conducting exercises in which armored and infantry brigades, without continuous artillery support, advanced quickly rehearsing an encounter battle.[2] Montgomery, who left for North Africa before the revived raid took place, adapted quickly once he examined the lessons learned by Eighth[1] Army in the desert, but no one with such experience was available to critique the plan for Rutter. A decision to limit the time ashore to one tide, seven hours further confused the plan as no changes to the intended objectives were made. Weather conditions and a German attack on landing ships led to the cancellation of Rutter. The soldiers were sent on leave until mid August when they were hastily recalled to take part in what was now called Operation Jubilee. The only significant change in the new plan was to use commandos instead of paratroops to take out the coastal batteries on the flanks. This was an improvement as commandos were far more experienced than paratroopers in 1942.

On the morning of 19 August, a naval task force of 237 ships and landing craft including six small destroyers reached the coast of France. More than 6,000 men, 4,963 of them Canadians, were committed to the action. There were small successes by the British C[2] ommandos and by Canadians at Green beach in Pourville, but at Blue Beach, Puys, and on the main Dieppe beaches effective action was halted by artillery and mortar fire. When the last survivors escaped 901 Canadians had been killed in action and 1,946 taken prisoner There were also 515 naval casualties and 300 among the British commandos. The Dieppe air battle was thought to be successful both in terms of protecting the Navy and defeating the Luftwaffe so the RAF and the Royal Navy saw the raid as a victory for their services. The army and combined operations headquarters claimed important lessons had been learned. Few historians have agreed.

The Prime Minister was scheduled to deliver a radio address on the evening of 19 August announcing new regulations in National Selective Service. With news of the raid coming from London, he began with a brief reference to Dieppe:

I am speaking to you on a memorable day. You will have learned that after long months of training Canadian soldiers from Britain have been in action against the enemy. We know how eager the army overseas has been to share in the actual combat with their comrades in the navy and air force. We are proud to hear that our troops had the foremost place in the raid on Dieppe. The news of any action should not be allowed to destroy our sense of perspective… We have reached one of the gravest hours in history. The Germans are advancing into the richest areas of southern Russia. The advance threatens to cut Soviet communications with the forces of the United Nations in Persia… and with forces in the middle east….

After listing a series of other challenges at sea and in the Far East, Mackenzie King declared that “the magnitude of the danger must increase our determination. Every citizen must make his most useful individual contribution”. This did not mean compulsory service overseas but rather new rules on the effective use of manpower in Canada by cutting down on non-essential production and services.[3]

Further news of the raid reached Canada the next morning. A statement issued in London described heavy losses on both sides without providing details. A special bulletin from Berlin reported the defeat of the invaders and the capture of sixty Canadian officers and 1,500 men. The next day it was clear that these were close to the actual numbers and included men from the Fusliers de Mont Royal. A Le Canada editorial, headed “FMR Salut,” declared that, “French Canada is proud of the FMRs”. Similar comments appeared in all the French-language dailies. The Star described the “reconnaissance in force as one of the most glorious incidents in the story of Canada’s arms showing the magnificent courage and fighting spirit of the troops.” The editor added that the FMRs will now “look to Quebec to restore their sadly thinned ranks.”

Ross Munro, the Canadian Press correspondent who had been on the raid, toured all cities which were home to Dieppe regiments presenting an heroic version of the day’s events. His talk at the Montreal Forum focused on the FMRs and the bravery of Lieutenant-Colonel Dollard Menard, who had continued to lead his men after being wounded. According to Munro, who was not in fact an eyewitness to the FMR landing, “nothing could have stopped the French Canadians.”[4]

Newspapers generally stuck to the themes of heroes and lessons learned but La Patrie, now edited by Letellier de St. Just, questioned the purpose and conduct of the raid. In a column of 16 September, St. Just argued that Canadians had the right to discuss the way their troops were used by the British high command. The disproportionate number of soldiers taken prisoner suggested that if the purpose of the raid was to learn about coastal defences why were so many troops landed. “Do we need to lose 3,000 men,” St. Just continued, “to discover that air bombardment is necessary.” He warned his readers that the Tory press was linking the losses at Dieppe to a renewed campaign to impose conscription for overseas service.

In time Quebecois nationalists would pick up on St. Just’s theme viewing Dieppe as an unnecessary sacrifice of French Canadian lives, but in 1942 the official explanation of an accidental encounter with a German coastal convoy as the primary cause of the heavy losses was generally accepted.[5] The view that Dieppe was more heroic triumph than tragic mistake was reinforced on the 2 October, when 178 Canadians including twenty-eight from Montreal received awards for bravery. Stories on the FMR’s commanding officer and the battalion’s chaplain, Father Armand Sabourin, were widely reported. A company of the Black Watch as well as the mortar platoon also participated in the raid but their experience at Blue beach did not lend itself to glorification and was rarely mentioned.[6]

On 16 October, the return of a number of men wounded at Dieppe led to an extraordinary demonstration of affection and pride in the city’s heroes. On short notice, thousands gathered at Lafontaine Park to welcome the FMR wounded. Premier Godbout and Justice Minister St. Laurent were there to welcome the veterans who were greeted with waves of applause. The event was reported, accurately, as a sincere spontaneous manifestation of respect for their heroes. For Montreal, in 1942 Dieppe was a triumph as well as a tragedy.

English-speaking Montrealers, particularly those from Verdun were equally enthusiastic about the return of George ‘Buzz’ Beurling, Canada’s best known fighter pilot. Born in Verdun in 1921 of Swedish and English parentage, he had learned to fly as a teenager. Lacking high school graduation credentials he was refused entry into the RCAF so he traveled to England to join the RAF beginning as a Sergeant pilot in 1941. During the defence of the island of Malta, Beurling flew a Spitfire and was credited with the destruction of twenty Italian and German aircraft He was awarded a Distinguished Flying Medal in July 1942 and a bar to the medal in September. One month later, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, the citation describing Beurling as a “relentless fighter whose determination and will to win has won him the admiration of his colleagues. This officer has set an example in keeping with the highest traditions of the Royal Air Force.”

Beurling returned to Canada in November 1942 to promote the war savings loan in a cross-country tour. After a reception in Ottawa he arrived in Montreal to be met by crowds lining the streets especially between Windsor station and the Verdun auditorium where 6,000 men, women and children gathered to greet him. The CBC broadcast the event nationally. Beurling was notably nervous and spoke briefly at the auditorium, but on a visit to Verdun high school where he had been a student he was relaxed and approachable, enjoying his status as a matinee idol with the students.[7]

On 6 July 1942, a German U-boat torpedoed three ships in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence setting off a minor political crisis in Ottawa. Censorship kept the news out of the press until the Member of Parliament for Gaspé used his parliamentary privileges to report the sinkings. Minister of Naval Services Angus McDonald then decided to limit censorship so that “Canadians could be informed of the presence of U boats in Canadian territorial waters”. The Prime Minister seems to have welcomed the decision to publicize the battle of the Saint Lawrence, drawing attention away from the vote on Bill 80 authorising conscription for overseas service. When isolated attacks continued, a secret session of parliament was held followed by a decision to close the Saint Lawrence to shipping. The public would only learn of the closure indirectly and few understood the scale of losses: twenty-one ships, including two Canadian naval vessels, with no U-boats accounted for.[8] There was no attempt to censor the news about the sinking of the SS Caribou, a passenger ferry between Nova Scotia and Newfoundland on 14 October. The loss of 137 lives, including fourteen children, was widely reported bringing the war much closer to home.[9] No one except senior naval officers understood how successful the U-boat wolf packs were in 1942 and there was no discussion of the countermeasures that would lead to an allied victory in the Battle of the Atlantic in 1943.

Montreal newspapers also provided detailed coverage of what Le Devoir called the battle of Outremont, a by-election involving the new Minister of National War Services, retired Major General Leo Lafleche and Jean Drapeau, a young Ligue lawyer. Lafleche had been a deputy minister and was on record as supporting a total war effort. The Liberals held the seat with a two-to-one margin but nationalists claimed that Drapeau won the FrenchCanadian vote while Lafleche relied on Anglo and Jewish voters.[10]

During 1942, Canadians took an increasing interest in the role of RCAF aircrew in the bomber offensive. Canadians served in RAF squadrons so stories were about Bomber Command with notes on individual Canadians. The RAF was unable to inflict significant damage in 1941 due to fundamental problems in navigation and target identification. Evidence from air photos, analyzed late in the year, demonstrated that only one in five night bombers got within five miles of the target so some method had to be improvised until better technical aids were available. Air Marshall Arthur Harris, who took command in February 1942, came to the conclusion that his force must concentrate on targets close to water features that could be found in moonlight. These would be bombed by concentrated streams of aircraft. The first attack, 3 March 1942, was on the Renault truck factories located just west of Paris in an identifiable loop of the River Seine. With good visibility and surprise, 235 aircraft caused a level of damage to factories and nearby workers houses never before achieved.[11] Subsequent raids on two German Baltic ports, Lubeck and Rostock, on 28 March and 23 April, were described accurately as Coventry-scale attacks using incendiaries as well as high explosive bombs. Then on the night of 30/31 May, Harris cobbled together 1,000 bombers to strike at Cologne on the Rhine. While there was some concern in Montreal about the Renault Paris raid, based on reports from Vichy, the attacks on German targets were widely praised.

By May 1942, more than 21,000 men, the majority Canadians, had completed aircrew training and thousands more would graduate in the next months. Long waiting lists for entry meant that Canadians under twenty-five who were high school graduates with junior or senior matriculation were the preferred candidates.[12] The honour rolls of the Protestant high schools in Montreal indicate strong preference for the RCAF. West Hill high school, in the city’s west end, lists more than 700 graduates serving in the Air Force in 1943 as compared to 500 in the army and 200 in the Navy. The Protestant School Board, reacting to student demand, established air cadet squadrons in each of its high schools and made participation compulsory for boys from age fifteen. Students could only opt out if they joined army or navy cadets.[13] Montreal’s Jews, who were overrepresented in the city’s high schools, were prominent among the cadets who subsequently enlisted in the Air Force. Nationally forty-five percent of all Jews in the armed forces were in the RCAF reflecting the experience in Montreal.[14] Completion of air cadet training meant that at age seventeen-and-a-half teenagers could join the RCAF and skip enrollment in the initial training schools though they could not fly until age eighteen.

The RCAF operated in English at all levels and French Canadians who were not fluently bilingual before entry were unlikely to be able to compete. An eight week pre-basic training English course was established in Quebec City in 1941 but it did little to change the situation. The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan established a number of stations in Quebec but few French Canadians attended. The daily diary and station magazine at RCAF Victoriaville, for example, depicts an English -Canadian unit with students from Poland, Czechoslovakia and a few French Canadians set down on the edge of a friendly French Canadian town.[15]

The importance of the RCAF to Montreal’s English-language community is evident in the newspaper coverage of both operations and casualty reports. La Presse and Le Canada featured items about French Canadians in the air force but otherwise coverage was largely limited to Canadian Press stories. The announcement in October 1942 of the plan to establish a Canadian Group as a distinct national component of Bomber Command was welcomed but delaying the organization until January 1943 allowed the news to fade away. La Presse applauded the creation of a French-Canadian unit to be known as the Alouette Squadron and established a comfort fund to accept donations. Thereafter photos of the members of the squadron were frequent.

The beginning of Eighth Army’s offensive in North Africa on 23 October was described in all newspapers but there was no expectation of a decisive victory. After two weeks of intense conflict Rommel’s army began a withdrawal, but by then the Anglo-American landings in French North Africa and the Battle of Stalingrad dominated the news. It would take time and messaging before the Second Battle of El Alamein and Bernard Montgomery would become central to the British and Canadian narrative of the war.

Hitler’s decision to occupy the Vichy-controlled zone of France, 11 November, led both Canada and the United States to sever diplomatic relations with Vichy. The French Canadian political class ceased to openly embrace Pétain but did not support De Gaulle. A new French leader, General Henri Giraud who, under American pressure, De Gaulle agreed to accept as Co-President of the French National Committee of Liberation, was adopted by French Canadian nationalists and Liberals. Giraud had been captured in 1940, escaped prison in 1942 and, on arrival in Vichy, accepted the legitimacy of Pétain’s government. He was sufficiently conservative to approve of Pétain’s national revolution while willing to assist the Allies in defeating Germany. When Giraud visited Canada in mid-July 1943, he was met with considerable enthusiasm in Montreal greeted by crowds waving the French tri-colour, the kind of reception de Gaulle would not receive until 1967.[16]

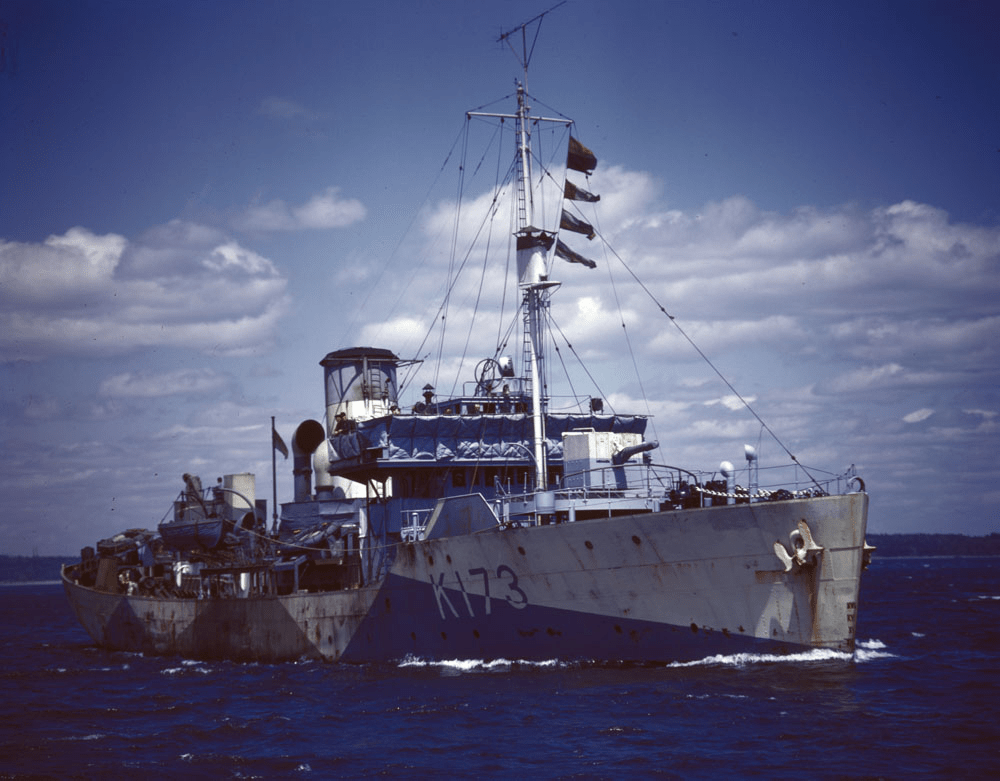

The role of the Royal Canadian Navy in Operation Torch ought to have been news of high impact countering criticism of the conduct of operations in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. Sixteen RCN corvettes were involved in the escort of the Torch convoys. One of them, HMCS Ville de Quebec, sank a German U-boat using depth charges before ramming the vessel. The ship’s captain, A. R. E. Coleman, a Montrealer, was awarded the DSO for the action but few attempts were made to dramatize the event or the subsequent work of the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve in the Mediterranean.[17] News of the arrival of Canadian army officers in Tunisia to serve with First British Army gaining battle experience did not impress newspapers like the Montreal Gazette which continued to offer criticism of the government and military for failing to involve the Canadian army in the North African campaign.[18]

The Gazette’s war correspondent, Lionel Shapiro, writing from London, provided a series of articles questioning the morale of the army in England. Shapiro claimed that if the present inaction continues “there will be no mutiny merely a general release of mental tension that makes them bright and eager troops.” Shapiro believed that morale could change in a moment if action began but was doubtful that any was imminent.[19]

On New Year’s Eve 1942, Montrealers marked the end of a tumultuous year with celebrations that brought soldiers and civilians together at the city’s night clubs, dance halls, hotels and churches. Despite an unusually severe winter storm with sleet and heavy snow paralyzing traffic, revelers and the faithful heard the bells ring out at the stroke of midnight. During 1942, full employment, overtime and workers shifting into better paying industries transformed the lives of many families who could afford luxuries long beyond their reach. Using 1926 = 100, the employment index for Montreal reached 167 by year’s end. These extraordinary increases were partly due to the entry of tens of thousands of married women into the paid labour force. Montreal manufacturers especially in the textile, garment, food and tobacco industries had always employed women but the vast majority were unmarried between the ages of fourteen and twenty-four. Employing married women of child-bearing age in factories presented very different challenges.

A survey conducted by Catholic action groups revealed that fifty-five percent of the 700 married women questioned worked more than forty hours a week and twenty-seven percent more than fifty. The Jesuit monthly Relations used this data to demand provincial legislation to limit the work day for married women to eighty hours and exclude women with children under sixteen from full time work. The legislature was also urged to take steps to monitor and improve working conditions.[20] No such restrictions were legislated. None of the unions active in the city took up this cause, continuing to focus on wages and union recognition.

In the first months of 1943 bloody drama unfolding at Stalingrad dominated the war news as the Red Army’s string of victories culminated in the surrender of the German Sixth Army on 2 February. Stories about the Battle for Tunisia were frequent but it was impossible to disguise the problems the Anglo-American forces were facing as the Germans sent additional troops to North Africa.

On 19 January Eleanor Roosevelt, a public figure in her own right, arrived in Montreal to speak in an event organized by the Quebec Committee to Aid Russia. A large crowd greeted her at Windsor Station where she praised Canada’s contribution to victory and described changing American attitudes that led to respect, admiration and goodwill towards Russia. That evening the prime minister and Quebec premier joined co-chairs Allen Bronfman and Phillipe Blais, as well as 12,000 Montrealers to welcome Mrs. Roosevelt. Her speech struck all the right notes for the predominantly Anglo and Jewish audience who gave her repeated standing ovations. The Soviet minister to Ottawa spoke briefly and he too received a prolonged ovation. Lauritz Melchior, the Metropolitan Opera tenor who was in Montreal for a concert, volunteered to perform and he sang a new composition “Russian Thanksgiving” as well as more familiar works. The press reported the event as major news with photos and human interest stories. Gratien Gelinas took advantage of the moment to announce that his “Fridolin 1943”, soon to open, would be a “third front of laughter.”

On 22 February, the Quebec Legislature began its annual session with a Speech from the Throne promising to make education compulsory and free up to age fourteen. This measure promised by the Liberals since 1940 was delayed until the responsible minister Hector Perrier was able to persuade Cardinal Villeneuve, as well as the majority of the Catholic Committee of Public Instruction to follow the Papacy’s acceptance of compulsory schooling in Europe. Perrier, a lawyer and Liberal Party activist, taught labour law at the University of Montreal while serving as a member of the Montreal Catholic School Commission and the Catholic Committee of Public Instruction. His support for teaching English in the primary grades and advocacy of a new history textbook to be published in both French and English aroused the wrath of the nationalists, but Perrier persisted. As Secretary of State in the Godbout government, he and his friend Victor Doré, the new Superintendent, avoided ideological issues focusing on the problem of keeping children in school. Using a statistical study prepared by a Jesuit priest, Perrier outlined the sharp contrast between the experience of catholics and protestants in Quebec. Just 41.4% of catholic children were enrolled in grade six dropping to 29.3% in grade seven. The comparable figures for protestants were 89.7% and 78.3%. Perrier’s empirical approach to a question that had divided French Canada for most of the century won the day and compulsory education to age fourteen began with the 1944 school year.[21] This measure was an enormous symbolic value but its immediate effects were limited. According to the Quebec Statistical Yearbook, the gradual reduction in the number of pupils in elementary schools—a result of the decline of the birth rate during the depression—limited additional funding for new schools and teachers, as well as the vibrant job market limited the impact of the legislation. The evidence suggests that the pattern observed in 1942 one in ten children under fourteen and one quarter of fourteen and fifteen-year-olds in the full or part-time labour force continued for the balance of the war and beyond.[22] The regulations of the National Selective Service that exempted children under sixteen from its control added to the pressure to send children to work. Situation vacant ads in La Presse and the Star specifically sought fifteen and sixteen-year-olds for a variety of jobs. It is likely that many fourteen-year-olds were hired as well.

Quebec nationalists paid slight attention to compulsory schooling or the war, directing their energy to the formation of a new party, Le Bloc Populaire Canadien. The Bloc was launched at the Marché St. Jacques before several thousand supporters. Ads for the meeting promised brief speeches by nine of the key figures including Maxime Raymond, who was to lead the federal wing of the party and Andre Laurendeau slated to become the provincial leader. Le Devoir, acting as a semi-official journal of the party, devoted two full pages to the event suggesting a new slogan for the party “Le Canada pour les Canadiens le Quebec pour la Quebecois.”[23]

The rest of the daily press ignored the Bloc publishing war news, rumours from the Casablanca Conference as well as stories about an elaborate navy tattoo staged at the Montreal forum. Music, precision marching, popular songs and donations for Aid to Russia attracted a large and enthusiastic audience.

The internal conflict between personalities and factions which would prove fatal to the Bloc was not apparent in 1943 when opposition to conscription and fear of centralizing power in Ottawa were themes that all nationalists could unite behind.[24] Elements in the movement that might have supported the progressive agenda of the Godbout government—compulsory education, votes for women, the nationalization of Montreal Light Heat and Power and measures of cultural nationalism—preferred to pursue their own quest for power.

The publication of the Marsh Report on Social Security in March 1943 attracted some attention in political circles especially with regard to his argument about the need for massive public expenditure in the first year after the war.[25] His proposal for family allowances and health insurance was mentioned but these ideas were not new and no one seems to have believed they were likely to be implemented. Social security measures were developed from a concern for a post-war recession and its political consequences not from popular pressure.

On 10 July, news of the invasion of Sicily by an “Anglo-American-Canadian” assault force brought the war much closer to home. Politicians, editorial writers, war correspondents, Canadian generals and especially the Minister of National Defence wanted Canadian troops in action in 1943 and the British agreed to substitute a Canadian division and tank brigade for British units training for “Operation Husky.”[26] This led to dramatic changes in the pace of training and the weaponry available to the Canadians. The armoured units, including the Three Rivers Regiment which had recruited in Montreal, were introduced to the Sherman tank while the infantry battalions obtained the six-pounder anti-tank gun and the PIAT, a British version of the bazooka. Rehearsals for an assault landing were held in Scotland before the Canadians sailed directly to Sicily.[27]

Censorship prevented the identification of the division involved until 31 July when correspondents were allowed to state that the First Canadian Infantry Division was “leading the push inland in central Sicily.” Ross Munro’s Canadian Press dispatches were translated so all the city’s newspapers printed the same stories including his account of the epic ascent of Assoro’s 1,500 yard cliff face by an “Ontario Regiment”.

In summing up the Canadian role in Sicily, Munro described a series of brilliant actions including the “daring night crossing of the Simeto River” by the Royal 22nd Regiment in operations to crack the Etna Line, but in Montreal there was profound disappointment that none of the city’s regiments were involved.

Reporting on Sicily had to compete for space with news from the Eastern Front where the largest tank battle of the war, Kursk-Orel, was underway. The Soviet counter offensive that began on 12 July, a turning point in the land war, was reported as a decisive defeat for Hitler. Stories also began to appear about the transformation of the Battle of the Atlantic as the Allies gained ascendancy over the U-boats but censorship prevented discussion of the problems facing the RCN.

The series of bomber attacks in late July on the port of Hamburg, which resulted in a firestorm and heavy loss of life, also got extensive coverage. The raids became controversial after the war but in 1943 they were greeted with satisfaction and expressions of pride that RCAF 6 Group had participated in this victory over the enemy’s formidable defences.

For Quebec nationalists none of these events mattered as much as the two federal by-elections in Quebec scheduled for 9 August. Le Devoir provided extensive coverage of the Bloc campaign in the Eastern Townships riding of Stanstead and in Montreal-Cartier with passing reference to the two contests in Western Canada. Observers, including the prime minister, thought it might predict the results of a general election. All four seats were Liberal but public opinion polls had recorded a significant rise in support for the social democratic Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF). On election day the Liberals lost all four ridings, two to the CCF, one to the Bloc and one to the Labour Progressive candidate in Cartier, Fred Rose.

The front page editorial in Le Devoir began with the words “Le government est battu: il est battu partout”. Omer Heroux boasted that the Bloc had won Stanstead in the Eastern Townships and came within 150 votes of victory in Montreal- Cartier. He concluded:

Quebec’s Ministers must understand they no longer speak for the province … Neither the Communist or conscriptionist machine could suppress the 5,500 votes honestly given to the Bloc candidate Paul Masse.[28]

The vote in Cartier, a riding held by prominent Jewish Liberals since its creation in 1925, revealed new divisions in the constituency. Paul Masse, the Bloc candidate, claimed to speak several European languages and pitched his appeal to the “foreign element “as well as French Canadians. Masse made it clear that he was opposed to Canada’s participation in a British war as well as conscription. Lazarus Phillips, the Liberal nominee, was a prominent lawyer and natural successor to Peter Bercovich and Sam Jacobs, the previous members. The CCF persuaded the party’s national secretary, David Lewis, who grew up in the riding before attending McGill law school and Oxford as a Rhodes scholar, to run against Phillips hoping to capitalize on growing support for the party nationally. Nominating a well known non-Zionist and secular Jew suggests how out of touch the CCF and Lewis were with Montreal Jews who were closely following the horrible events tormenting and killing their compatriots in Eastern Europe.[29] The Canadian Jewish Chronicle carried frequent reports from Poland, the Baltic States and the Balkans describing mass executions of Jews alongside appeals to save refugees by allowing entry into Palestine. The Chronicle could not possibly support Lewis. It endorsed Phillips largely ignoring the third Jewish candidate Fred Rose, a Communist Party member running as a Labour Progressive. The vote split four ways with Rose, who benefited from popular enthusiasm for the post-Stalingrad advance of the Red Army, winning with less than one third of the vote. Masse came a close second, Phillips third, and Lewis a poor fourth. The Chronicle‘s post election analysis argued that no one had paid attention to Rose who had used the Aid to Russia campaign and the communist-dominated Victory Clubs to win the riding.[30]

The Cartier by-election occurred during an aircraft workers strike fought over the National War Labour Board’s decision to backdate the workers cost of living bonus of four dollars and fifty-cents a week to March 1943 rather than July 1942. This meant a considerable loss of income to the members of IAM Lodge 712 but there was overwhelming support for stopping work in a warm Montreal summer. The aircraft companies were innocent bystanders who made sure the workers were paid for the previous two weeks on the second day of the strike. The men and women went back to work after fourteen days without a settlement. Labour historians see this strike, which accounted for one fifth of all days lost in Canada in 1943, as evidence of great labour militancy, but the Montreal Star suggested it was a much needed summer vacation for a work force that had put in long hours for several years.

Citations

[1] The chapters in C.P Stacey, Six Years of War, p. 349-408 still provide the best and most balanced account of the Dieppe Raid. See also Greg Scott, Sacrifice for Success Dieppe to D-Day and Denis and Shelagh Whitaker, Dieppe Tragedy to Triumph.

[2] Terry Copp, The Brigade: The Fifth Canadian Infantry Brigade 1939-1945, (Stoney Creek, 1992).

[3] The full text of the speech is available online at Selective Service (canadahistory.ca)

[4] Montreal Star, 5 September 1942. An RCAF bomber crew on a cross-Canada tour was also featured.

[5] Beatrice Richard, “Dieppe: The Making of a Myth” Canadian Military History, Vol 21, No. 4 (2015).

[6] The Black Watch Company attached to the Royal Regiment for Blue Beach was in reserve but landed to be taken prisoner. See Roman Jarymowycz, The History of the Black Watch, Vol 2 1939-45 (Montreal 2022) p. 42-45.

[7] Montreal Star, November 10, 1942. See also Serge Durflinger, Fighting From Home the Second World War in Verdun Quebec (Vancouver, 2006) p. 43-46.

[8] Censorship prevented details of the losses from reaching the public. See Roger Sarty, War in the St Lawrence (Toronto,: 2012)

[9] Malcolm Macleod, “Death By Choice or Chance? U-69 and the first Newfoundland Ferry Caribou,” Newfoundland Studies, Vol. 12, No. 1 (1996): 1-15. M. Macleod,” Death By Choice or Chance? U-69 and the first Newfoundland Ferry Caribou” Newfoundland Studies 1996 (online)

[10] Le Devoir, 2 December 1942.

- [11] See Andrew Fletcher, “Bomber Command Raid on Renault Plan,” 2022, available at www.key.aero, for air photos of the aftermath.

See surviving air photos of the aftermath at key.areo.

[12] F J Hatch, The Aerodrome of Democracy (.Ottawa, 1983).

[13] West Hill High School Year Books 1939-1945. Courtesy of Wes Cross.

[14] Peter J Usher, “Jews in the Royal Canadian Air Force 1” Canadian Jewish Studies, Vol. 20 (2012) Online.

[15] See, “RCAF Station Victoriaville,” available through rcaf.info.

[16] Le Canada, 19 July , 1943.

[17] Shawn Cafferkty,” “A Useful Lot These Canadian ships: The Royal Canadian Navy and Operation Torch” The Northern Mariner , Vol. 3, No. 4 (1993): 1-17 online; and Le Canada, 26 January, 1943.

[18] R. Daniel Pellerin “Canadian Infantry in North Africa January to May 1943” Canadian Military Journal, Vol. 21, No. 3 (2016). online

[19] Montreal Gazette, 22 January, 1943.

[20] Germaine Bernier “Encore le travail feminin” Relations (1943). online

[21] J A Taylor, “The Honorable Hector Perrier and the Passage of Compulsory School; Attendance Legislation in the Province of Quebec 1940-1943” (MA Thesis, University of Ottawa, 1973) online. See also Fernand Harvey,” Le minister ministre Hector Perrier, l’instruction obligatoire et la culture, 1940-1944” Cahiers de dix, No. 65 (2011). (online).

[22] Dominique Marshall, The Social Origins of the Welfare State: Quebec Families, CompulsaryCompulsory Education and Family Allowances (Waterloo 2006), p. 125 ff. Marshall’s book, a translation of her Aux origine sociale de l’Etat-providence is a history of the impact of the two measures on Quebec families rather than an account of their origins.

[23] Le Devoir, 3 February 1943.

[24] Paul-Andre Comeau, Le Bloc Populaire 1942-1948 (Montreal, 1992).

[25] La Presse, 16 March, 1943.

[26] Brandey Barton, “Public Opinion and National Prestige: The Politics of Canadian Army Participation in the Invasion of Sicily.” Canadian Military History Vol. 15, No. 2, (200612) Online.

[27] G W H Nicholson, The Canadians in Italy, (Ottawa, 1956)online.

[28] Le Devoir, 10 August 10, 1943.

[29] David Lewis, The Good Fight (Toronto 1981), p. 226-228.

[30] Canadian Jewish Chronicle, 13 August 13, 1943.

One thought on “Chapter VI: Limited War 1942-1943”

Comments are closed.